06 Mar The Tagores and their Mansions

The contrasting tales of two Tagore Thakurbaris in Kolkata

The Tagore family were like the Medici princes of Kolkata. As civic leaders, merchants, philanthropists, musicians, artists and poets, they were the most prominent family in Kolkata and played a huge role in the cultural and intellectual life of the city.

The Tagores had migrated to Kolkata from Jessore (now Bangladesh) at a most opportune time. The city was growing rapidly on the back of the East India Company to become the nerve center of the British Empire and one of Asia’s leading ports. The family earned their fortune supplying Fort William and the ships that anchored on the Hooghly. And they invested their wealth wisely in buying land in the expanding city and in the countryside. There were several Bengali families which rose to wealth and prominence in eighteenth-century Kolkata, but the Tagores became the most famous.

Jorasanko Thakurbari was the ancestral home of the Tagores

The initial Tagore home was in Pathuriaghata in north Kolkata but sometime in the 1760s Nil Moni Tagore – the younger of the brothers – moved out and set up a new residence about a mile away, at Jorasanko.

Since then, the red-bricked Jorasanko Thakurbari has lived a storied existence, becoming a hub of Kolkata’s cultural life, with its celebrated residents achieving great things. This is where Rabindranath Tagore was born and where he died. Today, part of the Jorasanko home has been converted in to a museum and another part has the Rabindra Bharti University.

Jorasanko Thakurbari was the ancestral home of the Tagores and a hub for Kolkata’s cultural life

Jorasanko Thakurbari was the ancestral home of the Tagores and a hub for Kolkata’s cultural life

The thakurbari is in the middle of a typical Bengali neighborhood with sights and sounds that would have been familiar to Rabindranath in his day; hand-drawn rickshaws crowd the narrow streets, passers-by bow their heads at small roadside shrines, coolies balance bulging sacks on their heads, the jingling bell of a muri-wallah announces his arrival while gossiping pedestrians sip chai in clay khullars.

Though it was built mainly by “Prince” Dwarkanath Tagore with his considerable wealth, the Jorasanko thakurbari is remembered more for his illustrious grandson Rabindranath Tagore. After buying my entry tickets, I entered a large central courtyard on the ground floor ringed by green-shuttered rooms that overlooked it. There were groups of students sitting in clusters and the soft tunes of Rabindra sangeet filled the air. This was where the Tagore family organized its many cultural events with the city’s leading poets, writers, artists, intellectuals attending.

The famous Thakurbari courtyard was central to Kolkata’s cultural life

The famous Thakurbari courtyard was central to Kolkata’s cultural life

The family lived on the first floor, which is now a museum. I took off my shoes to climb the stairs, with the first room being Mrinalini Devi’s small and intimate kitchen (Rabindranath’s wife, who died before him in 1902) with her mud-oven and cooking utensils arranged on wooden ledges. Next to it was Rabindranath’s spacious bedroom. Large doors opened on to airy verandahs on either side, letting in breeze and light. Rabindranath slept on a low wooden bed, like a takht. His framed photo was propped up on the pillows.

Beyond this was the room where Rabindranath had died, breathing his last on August 7th 1941. His words were mounted on the wall:

“When I leave from hence let this be my parting word,

That what I have seen is unsurpassable.

I have tasted of the hidden honey of this lotus that expands on the ocean of light, and thus I am blessed…

Let this be my parting word”

That what I have seen is unsurpassable.

I have tasted of the hidden honey of this lotus that expands on the ocean of light, and thus I am blessed…

Let this be my parting word”

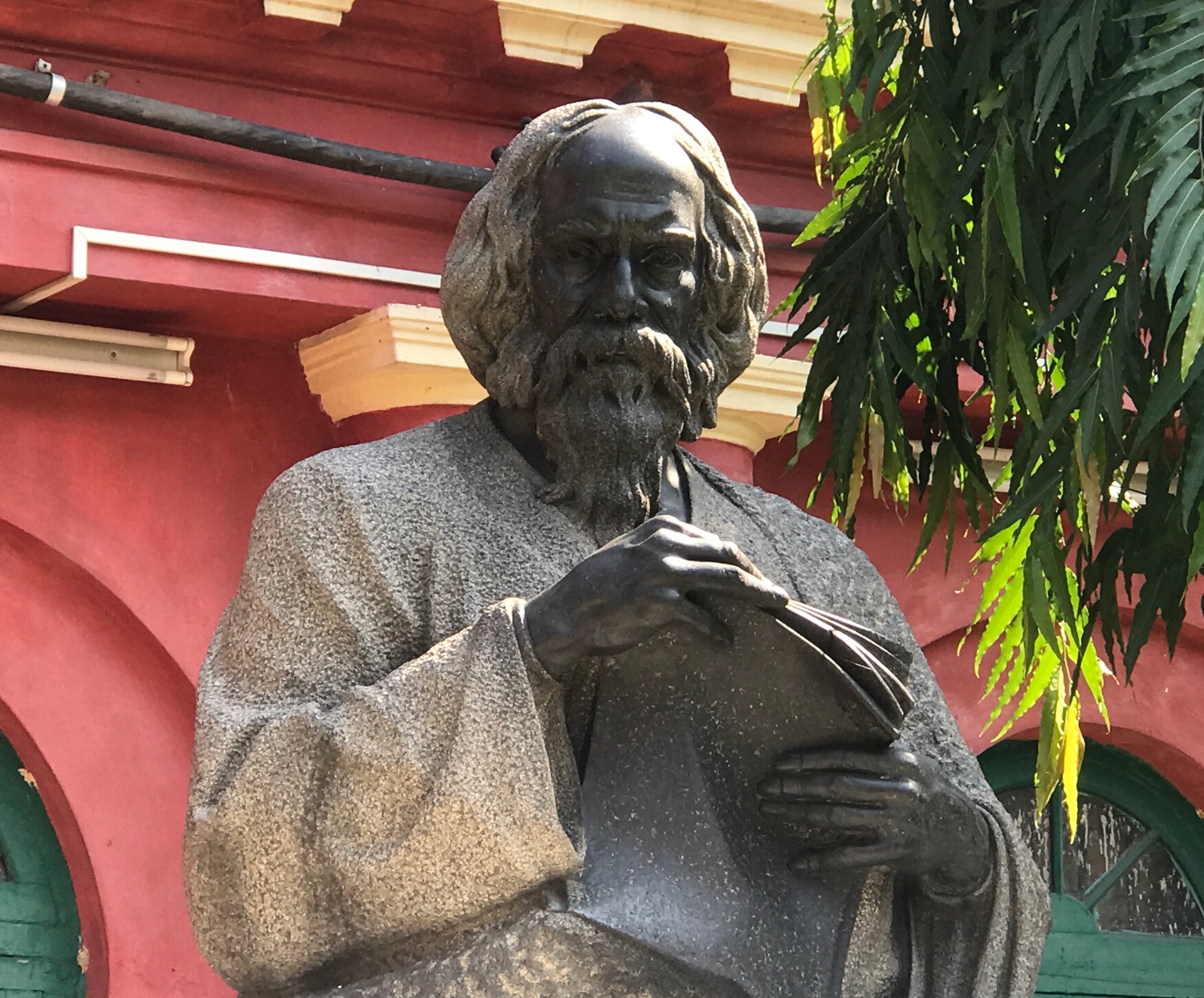

The celebrated Rabindranath was Jorasanko’s most famous resident; being born in this building as well as dying here

The celebrated Rabindranath was Jorasanko’s most famous resident; being born in this building as well as dying here

The most poignant part of the building was the “family maternity room” where the Tagore babies were born, including Rabindranath. It is in an adjoining block which looked visibly less grand than the main residential quarters. I was surprised by the smallness of the maternity room – I measured 8 paces long and 4 paces wide – and it was dark and windowless, with a small puja room attached. This was where the great Rabindranath had entered this world; to become one of India’s best-known sons, the first non-European to win the Nobel prize, the author of both the Indian and the Bangladeshi national anthems. And the man who’s poems are recited by students across our land…”where the mind is without fear and the head is held high, where knowledge is free…in to that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.”

“Prince” Dwarkanath Tagore; the merchant-prince who knew to party

Among the entire galaxy of the Tagore family-tree, I found Rabindranath’s grandfather Dwarkanath (1794-1846) to be one of the most fascinating.

Adopted by his uncle in early childhood, Dwarkanath had attended school in Calcutta where his principle, an Anglo-Indian named Mr Sherbourne, made such a big impression on him that Dwarkanath later settled a life pension on his teacher as a mark of respect. When he was just thirteen, Dwarkanath’s adoptive father died and he inherited property that yielded a comfortable income. But the young boy was more ambitious than that. Starting his career in various English firms as an apprentice, Dwarkanath eventually branched out on his own and in 1834 founded the Company that made him famous; Carr Tagore and Company, the first “equal partnership” firm between a European and Indian businessman.

The most-interesting merchant-prince Dwarkanath and me

The most-interesting merchant-prince Dwarkanath and me

Carr Tagore & Company did business in coal, tea, indigo and shipping and grew to be a real conglomerate. During the 1830s and 40s, Dwarkanath Tagore became the acknowledged civic leader of Kolkata. He was also a man who lived entirely on his own terms. Convinced that the future lay in the west, and that English culture and ways were worthy of being emulated, Dwarkanath approached British society and business as an equal, seeing himself as a bridge between communities and eager to mingle and work as partners with the English.

For his views, Dwarkanath paid a heavy price. As he cultivated friendships and wined and dined with Europeans, his own family distanced themselves. His wife Digambari and others at Jorasanko expelled him from the family home and Dwarkanath was obliged to live in a separate building to indulge his “impure” lifestyle.

Happy times at Belgachia Rajbari; now a silent ghost of its past

And so, to Dwarkanath Tagore’s revelry-house; the Belgachia rajbari.

Dwarkanath had bought this Belgachia villa in the 1820s for five lacs rupees, as a place where he could “shower hospitality on the social elite of Calcutta, both European and Indian”. The home had marble floors, elegant staircases, Roman statues, fine paintings….”on the left of the hall was a spacious verandah, decorated to resemble a Mongol tent, with leafy walls and garlands of flowers, in the center of which was a throne of crimson velvet and gold embroidery, with pillars of solid silver chased and inlaid with gold….outside was a spacious lawn with a meandering stream over which passed four rustic bridges…in the distance a life-sized Venus rising from an artificial lake…”.* You can get the picture.

A home that once hosted Calcutta’s who’s-who and a place to be seen.

A home that once hosted Calcutta’s who’s-who and a place to be seen.

As I drove to Belgachia from Jorasanko, I noticed it was a discreet 5 kilometers from the ancestral home, far enough to be away from the gaze of disapproving relatives. But sadly, all that remains of this fabulous rajbari now is its silent shell. Even though the mansion and its grounds are falling apart, I could still imagine the splendor of its past. The Belgachia villa is massive with about a hundred rooms and a magnificent entranceway topped by Corinthian-style columns that soared overhead. The portico is high enough for an elephant to enter, and I noticed it had a welcoming balcony tucked within its facade, useful for checking on who was visiting!

A soaring entranceway tall enough for an elephant; and with a welcoming balcony enclosed

A soaring entranceway tall enough for an elephant; and with a welcoming balcony enclosed Imagining the splendor of its past; intricate carvings support the balconies of Belgachia Rajbari

Imagining the splendor of its past; intricate carvings support the balconies of Belgachia Rajbari

Behind the building is a pond with marble benches from an earlier time still abutting the now-dirty water. This was where Dwarkanath hosted his parties, which were large and lavish with top officials and the city’s who’s-who. Locals would stand on the far side of this pond, taking in the razzle-dazzle.

I can quote from Emily Eden, the niece of Governor-General Lord Auckland, for whom Dwarkanath arranged a party on a cool November night in 1836…“with three hundred guests, including Calcutta’s leading European actors, singers and musicians, the chief justice, one or two generals…and most of the female beauty and fashion in Calcutta. The guests danced the waltz, quadrille and galop, and in the evening, multitudes of natives assembled for the fireworks.”* Emily was clearly a fan. Dwarakanath, she wrote, “is the only man in the country who gives pleasant parties.”

The pond around which the who’s who dined and waltzed. With curious locals on the far shore.

The pond around which the who’s who dined and waltzed. With curious locals on the far shore.Dwarkanath’s lonely death far from home

Standing on the grounds of his once-magnificent rajbari, I reflected on the fact that while Rabindranath breathed his last in the comfort of his Jorasanko home, his grandfather died a lonely death in far away England.

I had visited London’s Kensal Green Cemetery where Dwarkanath is buried. His grave was surprisingly well maintained (another irony….while his home falls to pieces his grave is well tended). A plaque inscribed on the base describes Dwarkanath as “the first Bengali merchant-entrepreneur to set up an Indo-British business partnership…a pioneer of press freedom…a signatory to the anti-sati petition and a friend of the 19th century social reformer Ram Mohun Roy. He was a personal friend of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert…feted by literary giants Charles Dickens, William Thackeray and many others.”

the well-maintained grave where Dwarkanath rests at Kensal Green cemetery in London

the well-maintained grave where Dwarkanath rests at Kensal Green cemetery in London

True to style, Dwarkanath’s visits to England were splendid occasions. On his first trip in 1842, he left Calcutta on board his own personal steamer with a physician, an “aide de camp”, three Hindu servants and a Muslim cook in attendance. And, his days in London included meetings with Robert Peel (the Prime Minister), Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, dinner appointments with industrialists, authors, politicians and the Directors of The East India Company.

While at a dinner party in London on a warm June evening in 1846, Dwarkanath suddenly took ill with severe shivering (possibly malaria carried over from Calcutta?) and never recovered. On August 1st, at the age of fifty-two, he died in his London hotel room. His body was bought to the Kensal Green cemetery in a convoy of carriages, watched over by his son, his nephew, his servants and some friends.

It was a lonely end to a controversial life. Dwarkanath had played many roles; the rich alms-giving Hindu, the western style entrepreneur, the exotic friend of English governors and royalty, the daring breaker of taboos. He was now buried forever in a quiet corner of London while his Kolkata villa slowly decayed.

*Pages 46-47, page 159 : “Partner in Empire : Dwarkanath Tagore and the age of enterprise in Eastern India”. By Blair B Kling.

How to get here:

-

- The closest metro to Jorasanko thakurabari is Green park, from where it is walking distance.

- If you drive, paid parking is available at the G-Centre mall opposite the thakubari entrance.

Jorasanko Information:

- Opening timings is 10.30am to 5pm, closed on Mondays.

- Entry ticket is Rs 20/- (and another Rs 50/- for taking photos)

- Toilet facilities

- No wheelchair access

Sources:

- “Partner in Empire : Dwarkanath Tagore and the age of enterprise in Eastern India”. By Blair B Kling. Published by The University of California Press

- “Memoir of Dwarkanath Tagore”. By Kissory Chand Mittra. Printed by Thacker, Spink & Co, Calcutta, 1870

- “Dwarkanath Tagore; A forgotten Pioneer”. By Krishna Kripalani. Published by National Book Trust, New Delhi

- “Wanderings of a Pilgrim in search of the Picturesque – Volumes 1&2”. By Fanny Parkes. Published by Pelham Richardson, 1850

- Begums, Thugs and Englishman ; the Journals of Fanny Parkes” By William Dalrymple. Published by Penguin Books, 2002.