14 Aug Saluting The Long-Forgotten Lascars

Kolkata’s Lascar Memorial pays tribute to some of colonial India’s original seafarers

Finding the Lascar Memorial was like hunting for the unknown, as if it had deliberately decided not to be found. That probably explains why it is among Kolkata’s least-known and least-visited monuments.

The Well Maintained Lascar War Memorial Is Among Kolkata’s Least-Visited Monuments

The Well Maintained Lascar War Memorial Is Among Kolkata’s Least-Visited Monuments

Which is a pity, because this memorial deserves much more. Not only due to the fact that the monument itself is so well-maintained, but also because it sheds light on an important passage of India’s colonial history, which if not spotlighted, could well be lost to the world.

The forgotten Lascars were colonial India’s first ocean sailors

Lascars were drawn mainly from Bengal and India’s west coast and were first employed by the East India Company in the 1600s for their ships returning home. This return leg to England would often be short-staffed, as British sailors regularly deserted the ship in India or died of disease during the journey. The lascars were the vital replacement crew.

The term lascar came from the Persian word “lashkar”, meaning army or camp follower. But the name also carried its own connotations, of “…a low, subordinated status and inferiority to white workers; if an unskilled Indian laborer was not a worker but a coolie and an Indian infantryman not a soldier but a sepoy, an Indian ocean sailor was not a seaman but merely a lascar.”*

By the mid-1800s there were an estimated 12,000 lascars working on English ships, about 18% of the total. They were hired under contracts much poorer than their European counterparts and paid less for tougher work. And their journeys were fraught with uncertainty, for once the lascars reached England, they were made to wait months for employment on a return ship, sometimes even abandoned by their employers and not provided proper lodgings.

It was a tough life, but they were pioneers in a way, being the first commonly seen brown faces on the streets of London. Some lascars stayed back, inter-married, started businesses and formed the beginnings of what is today Britain’s thriving south Asian community.

Lascars jump from the sail-ship to the steam-engine

There were two developments in the 1800s that boosted the demand for lascars even higher. The first was the opening of the Suez Canal, which shortened the distance from England to India, increasing the pressure for more sailings. And the second was the introduction of steamships to replace the older sail-ships.

Shoveling coal in the engine room of a steamship was hot and dangerous work, and shunned by European sailors. The lascars, on the other hand, coming from hot climates, were considered naturals at it. And beyond the heat of the engine room, the lascars were also the cleaners, cooks, store keepers, winchmen, oilmen, unloaders…doing all sorts of tasks on the ship.

The boss of the lascars was the serang, who was overall in charge of the crew, and had deep connections with his team. This was a critical position, as lascars knew no English and needed translators for communication. It was normal for the lascar to register for work at Kolkata (or Mumbai) and then wait at their village to be contacted, while the serang secured their contracts and then called them in time for the voyage. A round trip typically lasted between six and 12 months after which lascars would return to the village, with their salaries being paid at the origin port on completion of the journey to minimize chances of the lascar jumping ship.

To London to start a new life…

For those lascars who stayed back in England, being either abandoned by their employers or having jumped ship, life was a constant battle against poverty and prejudice.

In London, it was not uncommon to see dejected lascars “…shivering about the streets, wet and half naked, exhibiting a picture of misery little creditable to the English nation”. There was pressure on the East India Company to act, and in 1856, with the help of local charities, the “Strangers Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders” was opened in the docks area of London.

This was a lodging house for lascars, with the purpose of getting them recruited on ships returning east. The first donation of £500 was from no less than Maharaja Duleep Singh (the youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Lion of Punjab) and a regular income came from the British Government’s India Office. The “Strangers Home” had dormitories, baggage rooms, kitchens, a library and a resident missionary….and the fact that it had “stranger” in its name perhaps reflected the attitudes of the time.

Though the Strangers Home closed in 1937, I decided to track it down in London to relive the places where lascars would hang out. But there is no trace of it today. The original address has been converted in to apartment blocks, and the former docklands area – which used to be a vibrant if volatile community of Irish, Jewish and Scandinavian immigrants apart from lascars – was now covered with the gleaming skyscrapers of Canary Wharf, the sun glinting off the glass-cliffs of what is now London’s financial center.

What would the Lascars have made of this? Gleaming skyscrapers now dot their former stomping ground.

What would the Lascars have made of this? Gleaming skyscrapers now dot their former stomping ground.Back home in Kolkata, my day at the Lascar Memorial

So now back to Kolkata, where the relative obscurity of Lascar Memorial required Google Maps to overcome. I drove past the churning waters of Kidderpore docks, where a line of boats awaited unloading, to enter the calm and orderly streets of the naval area. In front of me was the Lascar Memorial, but that was far as I could get. The gates were locked, and the best I could do was stand outside the neat boundary fence for photographs.

Just a hundred yards from me were the imposing gates of the Netaji Subhas Naval Base. I walked up to it and was met by two smart uniformed seamen, in white navy outfit and caps, who were manning the main entry to the base. Their names were on their chest-tags – Tamang and Nayak. I explained my reason for visiting, gave a short impromptu lecture on who the lascars were and what the monument represents (they were curious and interested…) and handed them my Aadhar card as ID.

Tamang and Nayak were helpful. A discussion started on how best I could gain entry, interrupted by a call on Nayak’s phone. It was his wife complaining that their ceiling fan was not working. He solved the crises calmly, put down his phone, and was back, ready to share with me the world of the lascars.

A call was made to the office of the Master-Chief-Petty-Officer, with the explanation that a “historian” had come visiting and wanted permission to open and view the Lascar Memorial. I was granted permission with two conditions ; that Nayak would accompany me and I don’t take any photographs.

Walking Towards The Lascar War Memorial That Honors Indian Seamen Who Died Fighting in World War 1

Walking Towards The Lascar War Memorial That Honors Indian Seamen Who Died Fighting in World War 1

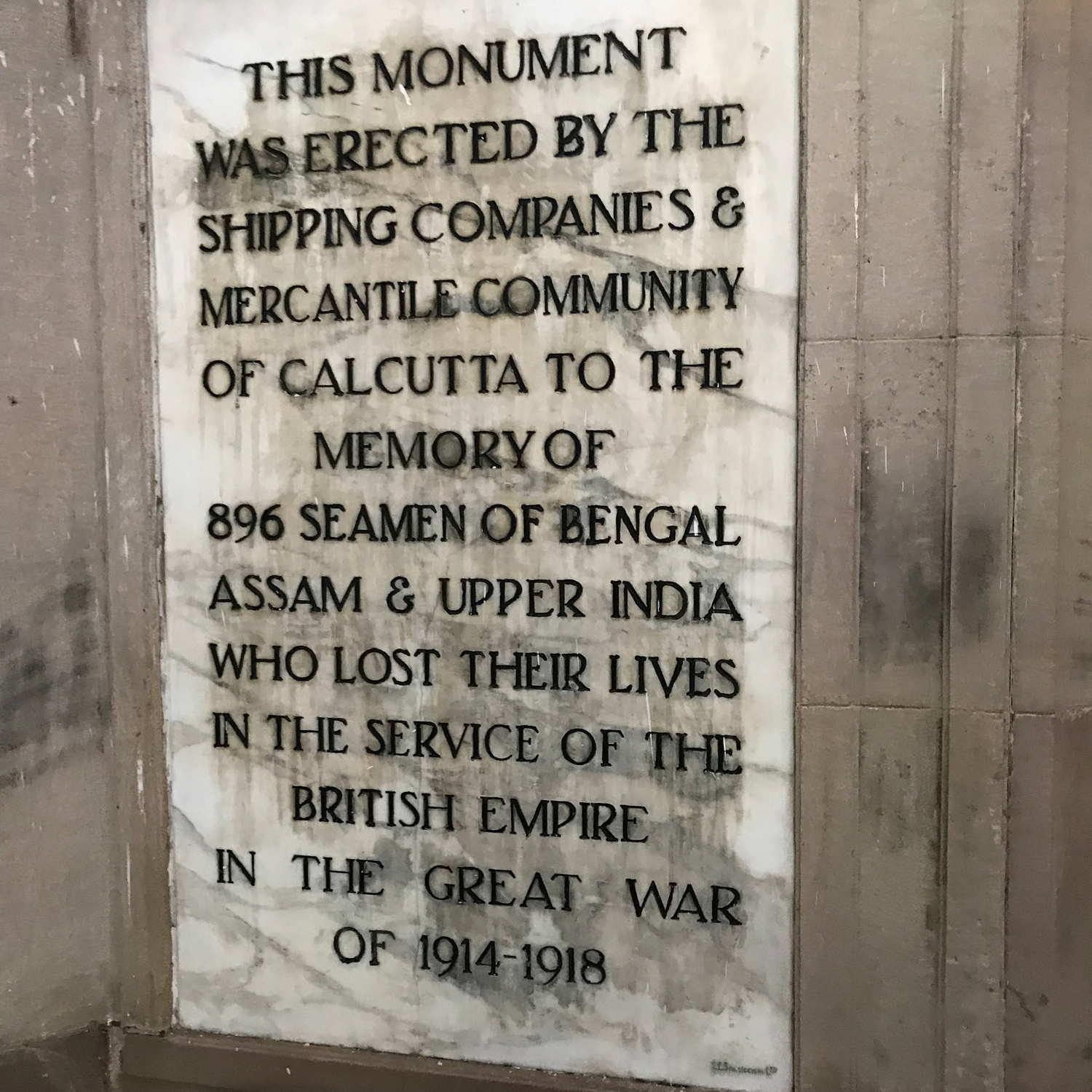

We walked onto the monument grounds and towards the memorial, past its neat green lawns and freshly painted façade. It’s important to understand that this was the Lascar War Memorial, built to honor the memory of 896 seamen from Bengal and Assam who lost their lives during World War 1, as opposed to lascars in general.

The memorial itself is about 100-feet high, and solid without being spectacular. I looked for the different features of the monument that I had read about and could now identify; the use of a dome and four mini minarets to provide it an Indo-Mughal style, prows projecting on each side resembling an ancient ship, undulating lines on the frontage symbolizing waves and the prominent use of chajjas with Indian style balconies.

The Lascar War Memorial was designed by William Keir, an architect with the East India Company, earning him a prize of 500 rupees for its design in a contest. It was paid for and erected by the “Shipping Companies and Mercantile Community of Calcutta” and completed in 1924, being inaugurated by Lord Lytton, the Governor of Bengal.

The Memorial Plaque Inside the Monument

The Memorial Plaque Inside the Monument

My friend, Leading Seaman Nayak, opened for me the cage-like door to the monument’s interior. We stepped in to a square room which smelt of the acidic odor of pigeon droppings, with their fallen feathers on the floor. A massive wrought iron staircase dominated the room, climbing to the top of the monument. There were three plaques on the facing wall; one stated that Lord Lytton, the Governor of Bengal, had unveiled this monument on February 6 1924. And another noted that the monument was erected by “the shipping companies and mercantile community of Calcutta” to the memory 896 Indian seaman who lost their lives in the service of the British Empire during 1914-18.

Stepping out, I spent a few minutes taking in the majesty of the surroundings. The memorial is most appropriately placed, standing on the banks of the slow flowing Hooghly and looking on in silence at the ebb and flow of a river which in many ways defined the lives of the people that it honors. I am sure that in days gone by, its glistening dome would attract the attention of seamen alighting at the nearby ghats, reminding them of the lascar martyrs. I wish though that this memorial would get the wider awareness and recognition that it deserves. Nayak, standing beside me, was having the same thoughts…“we can keep it neat and clean, but know little of the history or reason why”.

* “Lascars and Indian Ocean Seafaring”. By Aaron Jaffer (page2)

Sources:

- “Lascars and Indian Ocean Seafaring”. By Aaron Jaffer. Published by The Boydell Press

- “The Invisible Empire; White Discourse, Tolerance and Belonging”. By Georgie Wemyss. Published by Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- “Asians in Britain; 400 Years Of History”. By Rozina Visram. Published by Pluto Press, London

- Maritime History Archive, London