20 Jan Lodi Gardens’ Royal Landscape

Get Up Close and Personal with Stunning Fifteenth Century Afghan Tombs

If you are like most Delhi folk, catching hurried glimpses of Lodi Garden’s majestic monuments while rushing blindly past, then I suggest on the next occasion you pause and spend a few hours at the park. Its even better if you can combine this with a warm winter day, but even if you cannot…

Lodi Gardens is an oasis of green in the middle of Delhi’s frantic traffic. Like a superbly atmospheric necropolis, it is dotted with Lodi-era tombs full of hidden stories and forgotten secrets that peel back the layers of time to a dramatic and bygone era of Delhi’s history.

The Bara Gumbad Mystery; is it a Tomb? Or is it a Gateway? ?

The Bara Gumbad Mystery; is it a Tomb? Or is it a Gateway? ?

Lodi Gardens was created as recently as 1936. It was originally called Lady Willingdon Park and got its name Lodi Gardens after Independence in 1947. Prior to that, this area was on the outskirts of Delhi which explains the number of royal tombs that were built here. These tombs date from the late Sultanate period of the fifteenth century, before the Mughals arrived in India.

I spent a happy winter morning at Lodi Gardens, getting close-up views of its charismatic medieval monuments, all of which were extremely well preserved. There are five monuments within the park to explore, and you can follow me on the tour…

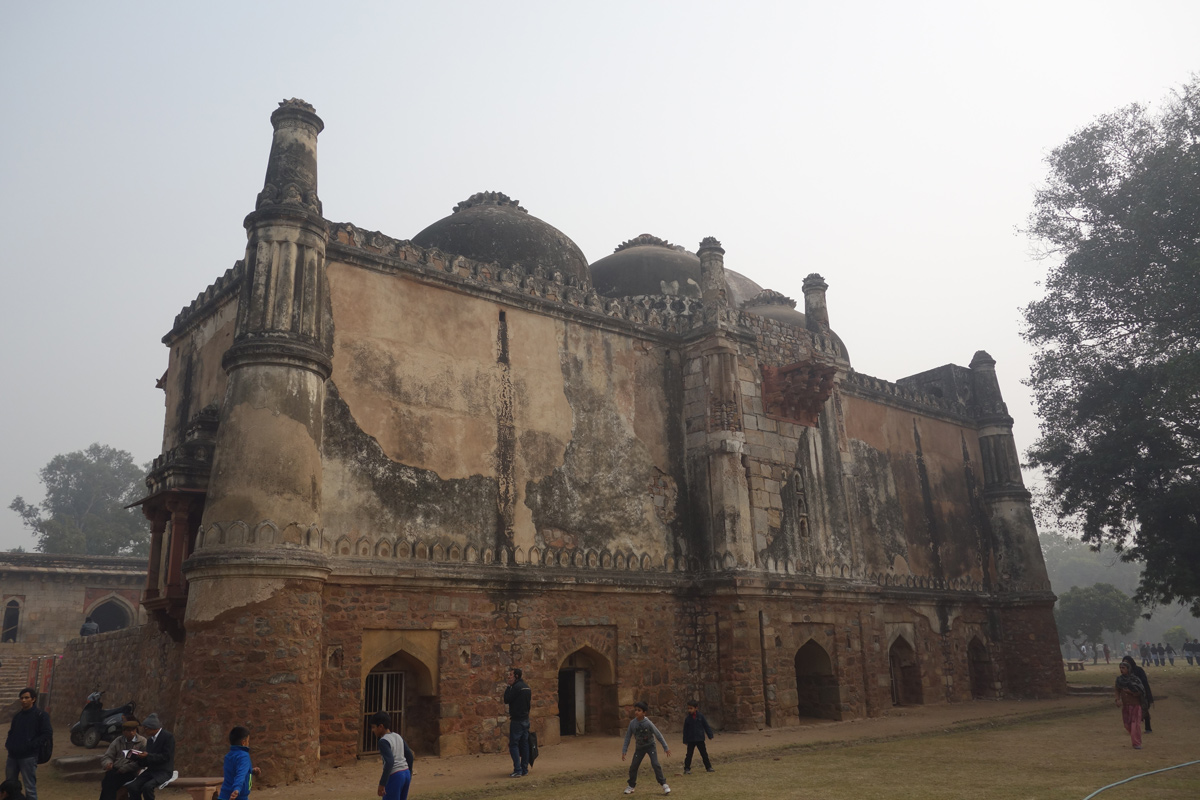

The Mysterious Bada Gumbad

The first of the grand buildings I saw on entering Lodi Gardens was the Bada Gumbad. I walked past picnicking families to get to the front, where a set of weathered stone stairs led up to an impressive entrance which was flanked on either side by an exquisite mosque and a timeless old serai.

Why Bara Gumbad was built is one of Lodi Gardens’ mysteries, with historians having different views. The plaque erected by ASI mentions it is a tomb with an unknown person buried in it, and the inscriptions over the monument’s four entrances back that up. Engraved over the gates are Koranic verses which clearly have funerary associations:

“and call not, besides God, on another God. There is no God but He.

Everything that exists will perish except his own Self.

To Him belongs the commands and to Him will you all be bought back.”

Everything that exists will perish except his own Self.

To Him belongs the commands and to Him will you all be bought back.”

Funerary Inscriptions are Carved in to The Four Entrances of Bara Gumbad

Funerary Inscriptions are Carved in to The Four Entrances of Bara Gumbad

The alternate theory is that Bara Gumbad – being square-shaped with openings on all four sides – would be very irregular for Muslim tombs of this era which tended instead to have distinct western walls with a mihrab (or niche, indicating the direction of prayer). Bara Gumbad could be the grand gateway for the Shish Gumbad that lies directly ahead, and which was built as the burial place for Bahlol Lodi, the powerful founder of the Lodi dynasty. Here too, the funerary inscriptions would be relevant.

We will never know for sure, and Bara Gumbad will remain an enigma. The fun is in exploring its imposing façade to imagine the possibilities of why it was built, and making up one’s own mind.

Sikander Lodi’s Timeless Mosque and the Adjoining Mehmaan Khaana

Flanking the Bada Gumbad is a most beautiful mosque which was built by Sikandar Lodi in 1494. It is packed with architectural features that are fine examples of the mingling of Islamic and Hindu traditions which took root during the Sultanate period.

You could look at the stucco decorations on the walls of the mosque, built from limestone plaster, which have both Islamic style geometric patterns as well as delicate Hindu floral designs. And, as with most Sultanate and Mughal era domes, the finials which crown the top of the each of the mosque’s three domes are lotuses with decorative edgings; the most eternal of all Indian designs.

Sikandar Lodi’s Mosque Adjoining Bara Gumbad is Packed with Interesting Features

Sikandar Lodi’s Mosque Adjoining Bara Gumbad is Packed with Interesting Features Delicate Decorations Made with Limestone Plaster, Above the Arches and Inside the Mosque

Delicate Decorations Made with Limestone Plaster, Above the Arches and Inside the Mosque

There is more about this mosque which makes it unique. Thanks to the historian Percival Spear’s excellent book on these Lodi Garden monuments, I knew exactly what to look for. Walking to the back of the mosque, past eager youngsters playing cricket, I could see four minarets which were thick at the bottom and tapering at the top, each of them divided in to four distinct layers. The architect had clearly used Qutub Minar as a model for these minarets, which is a characteristic distinctive to some mosques in Delhi and nowhere else in India.

Another Feature that Makes this Mosque Unique; Mini Replicas of the Qutub Minar Turrets

Another Feature that Makes this Mosque Unique; Mini Replicas of the Qutub Minar Turrets

Opposite the mosque and across a time-worn stone courtyard was a Mehmaan Khaana or guest house, which I entered to take a look. There were three wide rooms in a row and two smaller rooms, with shelves carved into the ancient walls for the storing of personal belongings and little niches for candles and lamps.

I sat here for a while, lost in imagining the people who would have stayed here, their stories, and where they came from….; what a fairytale sight this would be with the flickering oil lamps illuminating dark moonlit nights and muffled voices speaking in Hindi and Pashto and Braj Bhasa.

Shish Gumbad and its (ex) glimmering dome

Directly in front of the Mehmaan Khaana was the Shish Gumbad, so named for the “shisha” or glass-like panels that had originally adorned its dome. As I walked closer to the building, I could see the remnants of original blue-glazed ceramic tiles that once covered the whole of the top, creating what must have been an awe-inspiring shimmering azure blue.

The Shish Gumbad (Glass Dome) Was Originally Covered in Glazed Blue Tiles

The Shish Gumbad (Glass Dome) Was Originally Covered in Glazed Blue Tiles

Inside the Shish Gumbad were a number of graves, and who they belong to is another of Lodi Gardens’ secrets. They could be of Bahlol Lodi and his family, the Afghan Pashtun founder of the Lodi dynasty who ruled the Delhi Sultanate for a remarkably long thirty-eight years from 1451-89. But there is a rival to this claim, as another medieval tomb exists in Chirag Delhi – close to the Sufi saint Hazrat Chirag-e-Dilli’s mazhar – which is also considered Bahlol Lodi’s. I think we should just take this as another Lodi Garden puzzle.

Bahlol Lodi’s Eternal Gaze (?); The View From Shish Gumbad’s Crypt Looking Back on The Bara Gumbad

Bahlol Lodi’s Eternal Gaze (?); The View From Shish Gumbad’s Crypt Looking Back on The Bara Gumbad Akbar the Great’s Athpula Bridge

Unfortunately for Delhi, the great Mughal emperor Akbar had focused most of his glorious construction efforts on Agra, and so there are very few Akbar-era structures in Delhi. The Athpula bridge at Lodi Gardens is one of them.

As I approached the water body over which the Athpula bridge is built, I left behind the grace and antiquity of the Gumbads and was transported instead in to a noisy world of raucous birdlife. Parrots shrieked from treetops and busy ducks waddled past, while Cuckoos, Mynas, Bulbuls, Koels, Sparrows ducked and dived around me. In the middle of this chaos lay the calm Athpula Bridge.

Athpula bridge was surprisingly wide. Built to span a stream that ran through the area, it had an important road run over it to a nearby Mughal garden. I found a quiet place to take photos, away from the protesting ducks, then walked over Akbar’s bridge towards the fourth grand monument within the park; Sikandar Lodi’s fort-enclosed tomb.

Athpula Bridge, One of The Few Delhi Structures Built by Akbar

Athpula Bridge, One of The Few Delhi Structures Built by Akbar Sikandar Lodi’s Tomb Within a Fort

Sikandar Lodi’s mausoleum is the quietest and least visited building in the park, and perhaps because of this is also the most magical and enchanting.

Sikandar was the son of Bahlol Lodi and his wife Bibi Ambha, the Hindu daughter of a goldsmith from Sirhind in Punjab. Like his father before him, he too reigned for a long twenty-eight years (1489-1517) as Sultan of Delhi, and you can read more about Sikandar Lodi – as well as the other two Delhi Sultans buried in this park – in a later section which follows this blog.

This tomb was built by Sikandar’s son Ibrahim Lodi, in the typical octagonal style which was the fashion among later Sultanate rulers. The crypt is ringed by a veranda with thick stone pillars and a running chajja (overhang) to keep out the sun and the rain. And, it’s situated within a small fort, the walls, and bastions of which are fully intact today.

The Solid Fort-Like Walls and Bastions for Sikandar Lodi’s Atmospheric Tomb

The Solid Fort-Like Walls and Bastions for Sikandar Lodi’s Atmospheric Tomb

I entered the tomb through a small doorway and found his solitary grave in the center below the single dome. Above me, faded blue and green tiles with fine designs ringed the inside of the dome and I could see the red plasterwork, embedded with Koranic verses, from earlier decorations.

It was completely silent inside the tomb, with just the faint murmur of morning walkers outside the fort walls to remind me that I was in the middle of Delhi. I spent some reflection time in the peace beside Sikandar Lodi’s grave, alone with just a curious squirrel for company, soaking up the aura and atmosphere.

Looking Up at Another Era; Original Decorations Still Intact Inside Sikandar Lodi’s Tomb

Looking Up at Another Era; Original Decorations Still Intact Inside Sikandar Lodi’s Tomb The Iconic Crypt of Muhammad Shah Sayyid

The last of Lodi Garden’s fine monuments is also its most iconic and photographed. The tomb of Muhammad Shah Sayyid is the earliest-built structure in the park (1444), pre-dating the other Lodi-era buildings.

The Sayyids were a short-lived dynasty that ruled Delhi before the Lodis who eventually replaced them. They came to power in the vacuum that followed the 1398 sacking of Delhi by the feared Mongol warlord Timur “the lame”, which had left the city in smoking ruins and delivered a body blow to the power and prestige of the Sultanate.

The Sayyids reign lasted only thirty-seven years, with four different members of the dynasty ruling during this period. Muhammad Shah was the third Sayyid king, and had led the Delhi Sultanate for nine years (1434-1445) though his hold on power was always weak.

Yet, despite his feeble authority over a shrunken empire and the lack of funds for building grand tombs and palaces, Muhammad Shah’s crypt at Lodi Gardens is considered a masterpiece of late Sultanate architecture and the octagonal-tomb plan.

Like Sikander Lodi’s, here too we had a wide veranda running around the tomb with stone chajjas, but there was an additional lovely feature in ornate chattris (canopies) placed on the corners which the historian Percival Spear described as “gathering around the big dome-like chicks around a hen”

Muhammad Shah’s Tomb is a Fine Example of the Octagonal-Tomb Style; Notice the Chattris Gathered Around the Main Dome Like “Chicks Around a Hen”

Muhammad Shah’s Tomb is a Fine Example of the Octagonal-Tomb Style; Notice the Chattris Gathered Around the Main Dome Like “Chicks Around a Hen”

I climbed the worn steps of Muhammad Shah Sayyid’s tomb to find eight graves inside, a mix of male and female. At the center was Muhammad Shah and the rest were family members. As a reflection of the sad reality of the Sayyid’s rule, there was no marble work or decorations embellishing the graves. Even the mihrab, the enclosed western wall meant for prayer, was made plainly of stone without ornamentation.

Muhammad Shah Rests With His family; a Misfit Ruler for a Turbulent Age

Muhammad Shah Rests With His family; a Misfit Ruler for a Turbulent Age

Standing there, surrounded by Muhammad Shah and his family, I felt a deep and almost spiritual vibe. The atmosphere and mood were mystical, otherworldly; as if in a dargah or temple. And yet, just a few hundred feet from where I was, Delhi’s unceasing traffic whisked past outside the walls of Lodi Gardens, impatient and hurried. Two completely different worlds; all a part of incredible Delhi.

Why are the Lodi Garden Tombs Octagonal in Shape?

The use of octagonal tombs was probably inspired by Jerusalem’s “Dome of the Rock”, one of Islam’s most venerated buildings.

The octagon, which evolves from the squaring of the circle, symbolizes the reconciliation of the material side of Man, represented by the square, with the circle of eternity.

During the later Sultanate period in India, these octagonal tombs became the norm for royal burials and the best examples are these in Lodi Gardens. Later, with the arrival of the Mughals, this style was replaced by the Persian-inspired “charbagh” style tombs, the foremost example of which is the famous Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi.

Different Personalities, Different Styles; The Three Kings buried in Lodi Gardens

Most walkers at Lodi Gardens are probably not aware that they are in the royal company of three kings who together had ruled Delhi for seventy-five years

The three Sultans buried here – Muhammad Shah Sayyid, Bahlul Lodi and Sikandar Lodi – are all from the later Sultanate period but each had completely different personalities from the other.

The first of them, Muhammad Shah Sayyid became king at a time when the Sultanate was swirling in chaos and just about emerging from Timur’s sacking and devastation. The need was for a strong, dominant leader to exert his political will. Muhammad Shah was the opposite; easygoing and quick to seek the refuge of his harem, he was not overly concerned about his grip on power “…taking no measure to secure his possessions, but gave himself up to indulgence”.

Unsurprisingly, the disaffected nobles of Muhammad Shah’s court plotted to oust him. Muhammad Shah turned to Bahlul Lodi for help, who was then the Governor of Sirhind in Punjab. The Lodis were an Afghan tribe, strong in agriculture and horse breeding and highly valued as hardy, valiant soldiers. Bahlul Lodi intervened to suppress the nobles and save Muhammad Shah his crown, but he was the only real winner in this political mess. When Muhammad Shah died, Bahlul Lodi took over the Sultanate and established his own Lodi dynasty.

Bahlul Lodi ruled for thirty-nine years, an exceptional length in what was a very turbulent age. He was a cautious, deliberate man and unfailingly courteous in his dealing with others. This is what has been written about him; …” he accumulated no treasure, and executed his kingly functions without parade and ostentation…. In his social meetings he never sat on a throne…but seated himself upon a carpet.

“If at any time (his nobles) were displeased with him, he tried so hard to pacify them that he would himself go to their houses, ungird his sword from his waist, and place it before the offended party…saying “if you think me unworthy of the station I occupy, choose someone else” …if anyone was ill, he would himself go and attend on him…(but) he was exceedingly bold (in battle) …. from the day that he became king, no one achieved a victory over him”.

Bahlul Lodi died in 1489 at the age of eighty, from “excessive heat” or heatstroke, while returning to Delhi from a military campaign. He was succeeded by his third son, Sikandar Lodi, who was then only eighteen years old.

Sikandar Lodi is the third Sultan buried in Lodi Gardens. He was apparently, devilishly handsome “…remarkable for his beauty which was unsurpassed…whoever looked on him yielded his heart captive to him”.

Sikandar also had a long reign of twenty-eight years until his death at the still-young age of forty-six. He had inherited his father’s famous politeness and courtly good manners, having “….no desire for pomp and ceremonies, and cared not for possessions and magnificent dresses. No one who was profligate or of bad character had access to him.”

Along with his own frugal manners, Sikandar is said to have looked out for the poor. “…every winter he sent clothes and shawls for the benefit of the needy…. He ordained that twice a year he should be furnished with detailed accounts of the meritorious poor in his empire, whom he then supplied with means sufficient to support them for six months, each receiving according to his needs…”.

But it was not all good deeds from Sikandar, there were also shades of the not-good. According to an early seventeenth-century chronicler Abdullah, Sikandar could be somewhat of a bigot and was once told off by a cleric for his extremist views.

“…hearing this the sultan placed his hand on his dagger, and exclaimed, “you side with the infidels! I will first put an end to you…”. But the cleric stood his ground and replied, “Everyone’s life is in the hand of God…whoever enters the presence of a tyrant must beforehand prepare himself for death.” The sultan then rose and left in a huff. But he took no action against the cleric.”

How to get here:

-

- The main gate for Lodi Gardens is on Lodi Road, and the closest Metro station is Jor Bagh.

- On exiting the station walk towards Safdarjungs Tomb.

- Opposite Safdarjungs Tomb is Lodi Road

Information:

- The Park is open daily 6am-8pm.

- Good Toilet facilities (you pay Rs1/- to use)

- No wheelchair access

- Parking available

Sources:

- Percival Spear, “Delhi Its Monuments and History” (Delhi; Oxford India Paperbacks 1994, Third edition – updated and annotated by Narayani Gupta and Laura Sykes)

- Savita Kumari, “Tombs of Delhi, Sultanate Period” (Published by Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, Delhi, 2006)

- Abraham Eraly, “The Age of Wrath. A History of the Delhi Sultanate” (Published by the Penguin Group, India 2014)

- Archaeological Survey of India, “Monuments of Delhi” (Delhi, ASI, 2010)