Visiting a cemetery to track down silent graves is not everybody’s idea of a fun Sunday outing. Specially, if it is combined with a cold and miserable day. So I was not surprised that neither my wife nor the many friends that I called were keen to join me on this trip. “See you after” was the gist of it, so I was clearly alone for this one.

My visit was to the Kensal Green cemetery, one of the world’s first garden cemeteries opened way back in 1833. An impressive array of personalities are buried within its grounds, including “…Lord Byron’s wife, Oscar Wilde’s mother, Charles Dickens’ in-laws, Winston Churchill’s daughter, the surgeon who attended Nelson at Trafalgar, the creator of Pears’ soap, the legendary engineer Brunel…” And, what got my interest going, was that added to these notables were some Indian stalwarts ; Dwarkanath Tagore, the Bengali entrepreneur and grandfather of Rabindranath Tagore; Fanny Parkes who’s high spirited Indian adventures so scandalized British society and Maharani Jind Kaur, Sikh Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s fiery youngest wife who had fought two battles against the British in India.

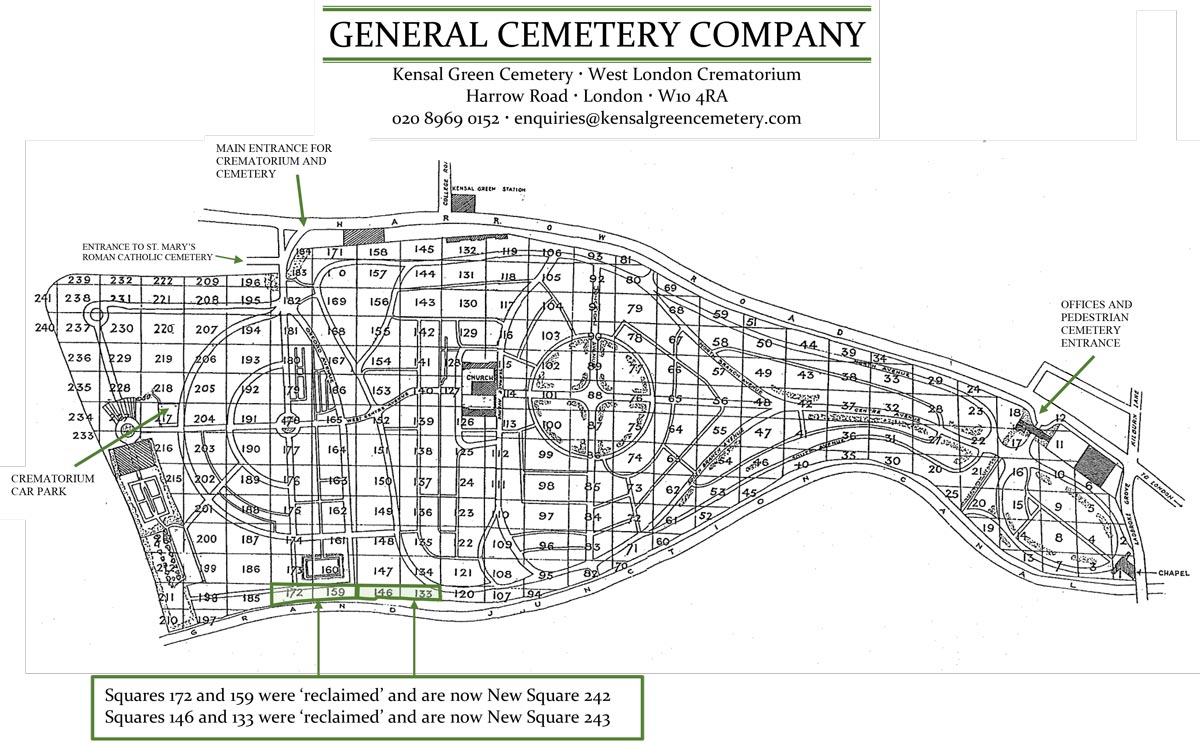

My homework had been meticulous and i knew exactly what to look for. Having called the Kensal Green cemetery and spoken with the polite and patient Nathan Pritchard, who had e-mailed me a map of the cemetery with the graves I was interested in boldly marked in green, I could not get lost ; “Fanny’s grave is located in square 50. And incidentally, Tagore is in square 16”. As it turned out, I did manage to get lost…. but more of that later.

It was a grey and rainy morning when I left home and scampered towards my neighborhood tube station, and as if by magic it was wonderfully bright and sunny when I emerged from the Kensal Green station. While I was being transported within the bowels of London Underground, the Weather Gods had dramatically changed their minds. Buoyed by the crisp winter sunshine, I walked down a hill skirting the cemetery walls, passed an old-world “William IV” pub – making a mental note to enjoy a beer there later – and arrived at the wrought-iron gateway to the cemetery.

The Kensal Green cemetery is divided in two parts, based on the faith of the persons buried. The majority of the grounds is consecrated by the Church of England and anchored by a big Anglican Church that dominates the center of the leafy grounds. There is a separate distinct section reserved for “dissenters” which has its own Dissenters Chapel. It is in this part of the grounds that Dwarkanath Tagore was buried.

Tagore’s grave was easy to find, and I was immediately struck by how well maintained it was. The swish of outside traffic had dimmed when I entered the cemetery and stood before his grave in silence. Someone had placed a recent bouquet of white flowers neatly on the side. A plaque inscribed on the base described Dwarakanath as “the first Bengali merchant-entrepreneur to set up an Indo-British business partnership…a pioneer of press freedom…a signatory to the anti-sati petition and a friend of the 19th century social reformer Ram Mohun Roy. He was a personal friend of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert…feted by literary giants Charles Dickens, William Thackeray and many others.”

I was standing by the final resting place of one of the “characters” of early Indian commerce. Dwarkanath Tagore (1794-1846) was born in Jorasanko in Bengal, the ancestral hub of the illustrious Tagore family. He had been adopted by his aunt as a child and was sent to Calcutta for schooling in Bengali and English, joining the Sherbourne’s School at the age of ten. The principle of this school was Mr Sherbourne, a much-respected Anglo-Indian gentleman who Dwarkanath obviously adored, as he later settled a life pension on Mr. Sherbourne as a mark of respect to his teacher. In 1807, when Dwarkanath was just thirteen, his adoptive father died and the young boy suddenly came to inherit property that yielded an income of thirty thousand rupees a year. This was enough for a comfortable life at the time, but it wouldn’t really count as a “silver spoon” fortune. However, for Dwarkanath it was enough and he never looked back. Starting his career by joining various English firms in Calcutta as an apprentice, he eventually branched out on his own and in 1834 founded the firm that made him famous; Carr Tagore and Company, the first “equal partnership” firm between a European and Indian businessman.

At his Company, Tagore was the boss. He provided the capital and directed all the business strategies, while Carr (an English Indigo trader in Calcutta) was a silent partner. This was a real conglomerate, doing business in coal, tea, indigo, shipping…enough for Dwarkanath to reap a fortune and become the mover and shaker of Calcutta society. By 1842, when Dwarakanath made his first visit to England, he was super-rich, leaving Calcutta in style on board his own personal steamer with a physician, an “aide de camp”, three Hindu servants and a Muslim cook. You could compare that to today’s tycoons, who at best muster pesky private jets or first class tickets! Dwarkanath arrived in London to pomp and ceremony, meeting with Robert Peel (the Prime Minister), Prince Albert and Queen Victoria. His diary was filled with dinner appointments with industrialists, authors, politicians and the Directors of The East India Company. Dwarkanath loved London, and from the tone of his writings in various diaries and letters he may even have flirted with the idea of settling in England and attempting a seat in Parliament.

It was on his second visit to England in 1846 that Dwarkanath’s health took a turn for the worse. While attending a dinner party on a warm June evening, he suddenly took ill with severe shivering (possibly malaria carried over from Calcutta?). Dwarkanath never recovered. With his loyal servant Hooly by his side, he was confined to his hotel for over a month, the fever not leaving him. On August 1st, at the age of fifty-two, Dwarakanath died in his room at St George’s Hotel on Albermarle Street. His body was bought to the Kensal Green cemetery in a convoy of carriages, watched over by his son, his nephew, his servants and some friends.

It was a lonely end to a controversial life. Dwarkanath had lived entirely on his own terms and made no bones about the fact that he thought the British Empire a noble undertaking, and English culture and ways worthy of being emulated. He saw himself as a bridge between communities, eager to mingle and work as partners with the English. This was bold for its time, and had led to Dwarkanath falling out with his own family and even his wife, who refused to have anything to do with him. But, though he died in London and is buried there, Dwarkanath’s legacy has shaped his home country India in so many ways. His son Debendranath Tagore was an eminent Bengali philosopher, and his grandson Rabindranath Tagore one of the best-known Indians, the first non-European to win the Nobel prize and the author of both the Indian and the Bangladeshi national anthems.

Given Dwarakanath’s appetite for a party, is it surprising that within the walls of the cemetery where he is buried are two more inhabitants with whom he had raised a toast? One was the novelist William Thackeray, who, along with Charles Dickens, Tagore had invited for a London dinner and subsequently written about in his diary. The other was Fanny Parkes, who had been a guest of Dwarkanath’s at his fabulous Belgachia mansion in Calcutta, and which she had written about in her memoirs. It was this same Fanny Parkes that I searched out next.

Fanny’s grave was in the oldest part of the cemetery, an area overgrown with foliage and rarely visited. The grass here was moist and blanketed with fallen rust-yellow leaves making the graves difficult to find. Curiously for a place of the dead, the grounds were visibly alive with frisky squirrels scampering across my path and black and white magpies hopping amid the greenery. Though I was reading the map of the cemetery to help navigate my way, I twice walked past the trail leading to Fanny Parke’s section of the cemetery without realizing it, before finally finding it on the third attempt. I felt disoriented and lost, knowing I was close to Fanny Parkes but not being able to find her. To add to my confusion, somewhere among the graves I had dropped my London Travelcard and spent frantic minutes searching the upturned headstones to get it back. It remained lost and I gave up, resuming my search for Fanny’s grave number 5975. Finally I found her, set in the final row, one of the oldest graves in the cemetery. The tombstone had faded and lost its lettering and the burial’s brick outline was just about discernable. The only way I knew I was in the right place was the map and the grave number located on it. In this grave in front of me lay both Fanny and her husband Charles Parkes.

Fanny Archer (1794-1875) was born in Wales, the daughter of an army man. At the age of twenty-seven, she had married Charles Parkes who was four years younger than her and a clerk with the East India Company. After marriage, the couple had left for India, landing at Calcutta’s Chandpal Ghat on the chilly morning of November 10, 1822. For Fanny, her new world was love at first sight. In no time she was living life to the full in Calcutta; managing her home with an array of servants, galloping her Arab stallion on the Maidan, learning Urdu and Hindi, and attending dinner balls with “Nawabs, Rajahs, Mahrattas, Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Mussalmans, and Hindoos”.

What fun it would be to have met Fanny. She was irreverent and curious, delighting in new experiences and making friends. Fanny’s free association with Indians and her respect for the local culture was met with sarcasm by her English counterparts. In this, she was really the last of a breed. During the twenty years that Fanny spent in India, British attitudes were hardening and racial segregation became the norm. Fanny’s adventuresome, freewheeling ways were sadly out of sync with where things were heading.

Fanny Parkes spent twenty years in India between Calcutta and Kanpur and Allahabad, as her husband took up different postings with the East India Company. She used her time to explore the whole of north India, publishing her memoirs “Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque” which has great insights in to Indian society specially as seen by a westerner. “Roaming about with a good tent and a good Arab (horse), one might be happy forever in India” she wrote. Fanny made friends with both princesses and commoners, visiting privileged zenanas and humble homes, and she wrote about them all.

One of Fanny’s friends was Princess Humanee Begum, the niece of Mughal Emperor Akbar Shah, with whom she stayed in Kasganj and shared hookahs while discussing life…“how gracefully she walks, straight as an arrow…In Europe, how very rarely does a woman walk gracefully…the body is as stiff as a lobster in its shell”*. Fanny rode horses in Fatehgarh in the Maratha-style with the feisty Baiza Bai, the ex Queen of Gwalior who had fought Arthur Wellesley in battle, and who “could not comprehend how an English lady on horseback could sit all crooked, all on one side, in the side-saddle”. Fanny was persuaded by Baiza Bai to change in to Maratha dress, and mount her horse “putting my feet in to the great iron stirrups, and started away for a gallop around the enclosure. I thought of Queen Elizabeth, and her stupidity in changing the style of riding for women. En cavalier it appeared so safe, as if I could have jumped over the moon”.*

Curiously, while Fanny lived this carefree life in India, society in England was becoming more fossilized specially for women. Fanny observed this, and wrote about it in annoyance. After sixteen years in India, in 1838 Fanny’s father died and she travelled back to England to nurse her ailing mother. She remained in England for three years till her mother too sadly died in 1841. For Fanny, it was difficult to adjust back to England. The place “looked so wretchedly mean, specially the houses”, and she ranted in frustration about the societal norms. On a visit to a horticultural show in Plymouth…”I went to the place alone, and the people expressed their surprise at my having done so – how absurd! as if I were to be a prisoner unless some lady should accompany me – wah! wah! I shall never be tamed, I trust, to the ideas of propriety of civilized Lady Log.”**

Fanny and Charles came back to England for good in 1845. Charles died in 1854, while Fanny lived on for another twenty years till the age of eighty-one, dying of “shingles and exhaustion” at her home in Cornwall Terrace in Regents Park. She was laid to rest in Kensal Green, in the same grave as her husband. I thought about what Fanny had felt of the Taj Mahal, when overcome with emotion on seeing the lovely building, she wrote ”adieu beautiful Taj… In the far, far west I shall rejoice that I have gazed upon your beauty ; nor will the memory depart until the lowly tomb of an English gentlewoman closes on my remains”. Lovely words, and so apt as I stood now in front of her grave. Rest in peace Fanny, animated admirer and lover and chronicler of India.

Kensal Green had opened a window on two extraordinary lives, and next on my list was an equally remarkable Maharani. Not many are aware of the connection that Kensal Green has with Sikh history. It was here, in the catacombs of the Dissenters Chapel, that the body of Maharani Jind Kaur, the youngest queen of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and mother of Prince Duleep Singh, was interred for a year before being taken by her son for her final cremation to Bombay. Jind Kaur’s plaque has pride of place on the walls of the Dissenters Chapel.

Maharani Jind Kaur (1817-1863) was the last Queen of Punjab, and had died in London at the very young age of forty-six. Yet, she packed in more experiences in her short life than most of us do in several lifetimes. Jindan Kaur was born to a humble family in Punjab, her father being the overseer of the royal kennels. Her rise from kennel-keeper’s daughter to Maharani of the Sikh Empire is fairytale-stuff. When still in her teens, Jind Kaur’s beauty caught the eye of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and she married the Sher-e-Punjab when she was eighteen. They had a son, Prince Duleep Singh, before Ranjit Singh died of a stroke in 1839 leaving her a widow at just twenty-one. After Ranjit Singh’s death, the boy-Prince Duleep Singh was placed on the throne and the fiercely protective Jind Kaur took control as Regent on her son’s behalf . She administered the Sikh Empire for three tumultuous years, containing palace intrigues and negotiating between different factions to get the house in order. All this while, the East India Company was knocking on the doors of her territories, spoiling for a fight. Punjab was the only big kingdom in India that was still independent and not in their control, and they were anxious to annex it.

The Sikhs and the English fought two wars in quick succession, leading to the end of the Sikh Empire (with it, the Koh-i-noor diamond plucked from Lahore and placed on the Queen of England’s crown). Queen Jind Kaur was imprisoned in the “impregnable” Chunar Fort near Varanasi while her son Prince Duleep Singh was bought to England, for a while personally looked after by Queen Victoria, and “anglicized” in every way. Jind Kaur did not see her son again for thirteen years, but she fought on. Making a dramatic escape disguising herself as a maid, she trekked over eight hundred kilometers through raging rivers and dense forests to reach Kathmandu in Nepal, where she was given refuge by Nepal’s Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Rana. Jind Kaur stayed in Nepal as a refugee-queen for eleven years, yearning for her homeland and her son as she got increasingly frail and her eyesight began to fail her.

Then, there was another twist to her extraordinary life. Jind Kaur’s son, Prince Duleep Singh, who was by now a strapping young man in England, decided he had enough of being denied his family and wanted his mother with him. He tried various means to reach his mother, sending a letter to her in Kathmandu which was intercepted by the British Resident, then hiring a courier, Pundit Nehemiah Goreh (quite a character, a Brahman convert to Christianity, living in Benaras) who too was intercepted and not allowed to meet the Maharani. Finally, Duleep Singh wrote directly to the British Resident in Nepal who took the decision that Jind Kaur had by now “lost much of the energy which formerly characterized her” and was no longer a threat. She was allowed to join her son on Jan 16th 1861 at the Spence’s Hotel in Calcutta and accompany him to England.

So it was that the Rebel Queen Jind Kaur, who had fought two bitter wars against the British on the battlefields in India, landed on English soil. She must have smiled at her kismet, being taken care of by the very power that had usurped her kingdom. Jind Kaur lived just two years in England, constantly reminding her son of his lost heritage, before breathing her last on the morning of August 1st 1863, peacefully in her sleep. She was temporarily buried in the Kensal Green cemetery for a year (as cremation was not recognized in England at the time), before her remains were taken by her son Duleep Singh to Bombay.

My day out at Kensal Green was enriching and filled with the little discoveries that I was so looking forward to. I had connected with the amazing lives of three persons who stitched together England and India in their own unique ways. I stepped in to the welcoming warmth of William IV pub and ordered myself a well deserved beer, settled at a table and watched the last visitors leave the cemetery. As i started typing out my thoughts for this blog, I thought of the three personalities who were buried within Kensal Green. They were each very different characters and yet they were similar in the boldness of their thoughts and pioneering spirit. Fanny Parkes had said it perfectly for all of them in the motto that she gave to her memoirs; “Let the result be what it may, I have launched my boat”.

* “Kipling Sahib” by Charles Allen, page 189

The cemetery’s wrought iron main gates; an entry in to quiet solitude and resting souls

The cemetery’s wrought iron main gates; an entry in to quiet solitude and resting souls Tracking down the graves of Fanny memsahib and Tagore sahib

Tracking down the graves of Fanny memsahib and Tagore sahib The well maintained grave of Dwarkanath Tagore

The well maintained grave of Dwarkanath Tagore The Many Striking monuments to the dead within the cemetery

The Many Striking monuments to the dead within the cemetery  The trail to finding Fanny Parkes, past unmarked graves in the oldest section of the cemetery

The trail to finding Fanny Parkes, past unmarked graves in the oldest section of the cemetery The mortal remains of Fanny Parkes; carefree admirer and chronicler of India

The mortal remains of Fanny Parkes; carefree admirer and chronicler of India The heritage-listed Dissenters Chapel, where Maharani Jind Kaur lay for a year

The heritage-listed Dissenters Chapel, where Maharani Jind Kaur lay for a year Maharani Jind Kaur’s plaque takes pride of place at the Dissenters Chapel in Kensal Green

Maharani Jind Kaur’s plaque takes pride of place at the Dissenters Chapel in Kensal Green