John Nicholson was born in Lisburn, Ireland in 1822, the eldest son of “earnest, upright, bible reading protestants”. He came to India when he was just a young boy aged sixteen to join the East India Company, and he died here at the still-young age of thirty five, mortally wounded in the battle at Kashmiri Gate. During the twenty-odd years that Nicholson spent in India, he truly established himself as the legendary “Hero of Delhi”, one of the most celebrated British East India Company officers with numerous tales and folklore surrounding his many exploits.

William Dalrymple, the historian, describes Nicholson as…“6 feet 2 inches in height with a long black beard, dark grey eyes with black pupils which under excitement would dilate like a tigers…a color-less face upon which no smile passed”. He had a commanding personality with a strong take-charge style of leadership, and was quick to violence, abhorring any form of what he perceived as weakness even from his superiors, which made him a difficult person to work with.

Nicholson served most of his military duties in India’s unruly North West. He fought in the Anglo-Afghan and Anglo-Sikh wars and served as District Commissioner in Punjab. Without a doubt, Nicholson’s vicious experiences in the North West colored his feelings for India. He was taken prisoner in the ill-fated 1842 Afghan war, and lost his brother in a horrific manner. L.J. Trotter, in his book “The Life of John Nicholson” describes the terrible scene of Nicholson being released as prisoner in Afghanistan, only to find his younger brother’s dead body with his genitals cut off and stuffed in his mouth.

“…the shock to John Nicholson must have been all the greater for the manner in which he first became aware of his brothers death. They were riding on rear-guard down the pass when they espied what seemed to be the naked body of a European gleaming to the right, some way off the line of march. Cantering to the spot, heedless of danger and of their chief’s orders against leaving the line of march, they found the corpse of a white man stripped of everything save a mere fragment of the shirt, and fearfully mutilated in true Afghan fashion about the base of the trunk. Nicholson gazed at the dead man and for the moment he could not speak. He had recognized the features of his own brother”.

One of Nicholson’s defining styles was his mastery of symbolic acts, and his perfect understanding of the power and impact of symbolism on local populations. There are many examples of him using symbolism to drive home the point of who was boss. Once, as Deputy Commissioner for Bannu (in todays north west Pakistan) “…he was riding through a Bannuchi village with his escort of mounted police and a few of the local maliks. As he passed along every villager saluted him except one, a mullah, who sat in front of the village mosque. Instead of salaaming him, he sat looking at the hakim with a scowl of open hatred (Nicholson was called hakim by the locals). As soon as the cavalcade had passed out of the village, Nicholson asked one of his orderlies if he had noticed the mullah’s behavior. Yes he had noticed it. “then go and bring him to my camp”. The village barber was sent for at the same time…”. Nicholson ordered the barber to shave the mullah’s beard before allowing him to return to the village, “…where the sight of a beardless mullah made a lasting impression, and became the talk of the whole district”.

Though Nicholson was feared for his violent and cruel streak, he also earned himself respect with the restless Afghan and North Punjab tribes for a sense of honor and for establishing much needed law and order in that territory. He had even inspired a cult, The Nikal Seyni, who literally worshipped him. On his part, Nicholson seems to have formed a mixed opinion of the Afghan character. He wrote “ …I must, however, mention some traits in the Afghan character, which I had full leisure to study during my imprisonment. They are, without exception, the most bloodthirsty and treacherous race in existence, more so than any one who had not experience of them could conceive; with all that, they have more natural, innate politeness than any people I have ever seen. Men of our guard used to ask us of our friends at home: ‘have you a mother? – have you brothers and sisters? – and how many?”. It was often been said to me by a man who (to use an expression of their own) would have cut another’s throat for an onion, “alas! alas! What a state of mind your poor mother must be in about you now; how I pity both you and her”, and although insincere he did not mean this as a jest…”.

With the onset of the 1857 revolt, John Nicholson was asked to march from Punjab to Delhi at the head of the Punjab Moveable Column and relieve the Delhi siege. On the way to Delhi he stopped at Jalandhar, ruled by the Maharaja of Kapurthala, where the local Province Commissioner Major Lake had organized a darbar. At this time, due to the revolt, British authority was vulnerable and nobody understood this better than Nicholson. There is an incident that took place at the Jalandhar darbar which aptly sums up Nicholson’s fearsome style of leadership and his innate grasp of symbolism. This is narrated by L.J Trotter in his book :

“…General Mehtab Singh, a near relative of the Rajah, took his leave, and as the senior in rank at the darbar was walking out of the room first, when I observed Nicholson stalk to the door, put himself in from of Mehtab Singh, and waving him back with an authoritative air, prevented him from leaving the room. The rest of the company then passed out.; and when they had gone Nicholson said to Lake “do you see that general Mehtab Singh has his shoes on?” Lake replied that he had noticed the fact, but tried to excuse it. Nicholson, however, speaking in Hindustani, said “there is no possible excuse for such an act of gross impertinence. Mehtab Singh knows perfectly well that he would not venture to step on his own father’s carpet, save barefooted; and he has only committed this breach of etiquette today because he thinks we are not in a position to resent the insult, and that he can treat us as he would not have dared to a month ago.” Mehtab Singh looked extremely foolish, and stammered out some kind of apology; but Nicholson was not to be appeased, and continued “if I were the last Englishman left in Jalandhar, you (addressing Mehtab Singh) should not come into my room with your shoes on”. Then politely turning to Lake, he added “I hope the commissioner will now allow me to order you to take your shoes off and carry them out in your own hands so that your followers may witness your discomfiture.” Mehtab Singh, completely cowed, meekly did as he was told. Indeed, Nicholson’s uncompromising bearing on the occasion proved a great help to Lake, for it had the best possible effect on the Kapurthalla people; their manner at once changed, all disrespect vanished, there was no more swaggering about as if they considered themselves masters of the situation”

It was incidents and tales such as these that created the lore around Nicholson’s personality.

The historic double arches of Kashmiri Gate, the scene of a momentous and bloody battle in 1857

The historic double arches of Kashmiri Gate, the scene of a momentous and bloody battle in 1857

John Nicholson charged through these gates to re-take Delhi, but lost his life in doing so

John Nicholson charged through these gates to re-take Delhi, but lost his life in doing so The battle scarred rear walls of Kashmiri Gate, with damage from cannon balls still visible.

The battle scarred rear walls of Kashmiri Gate, with damage from cannon balls still visible.

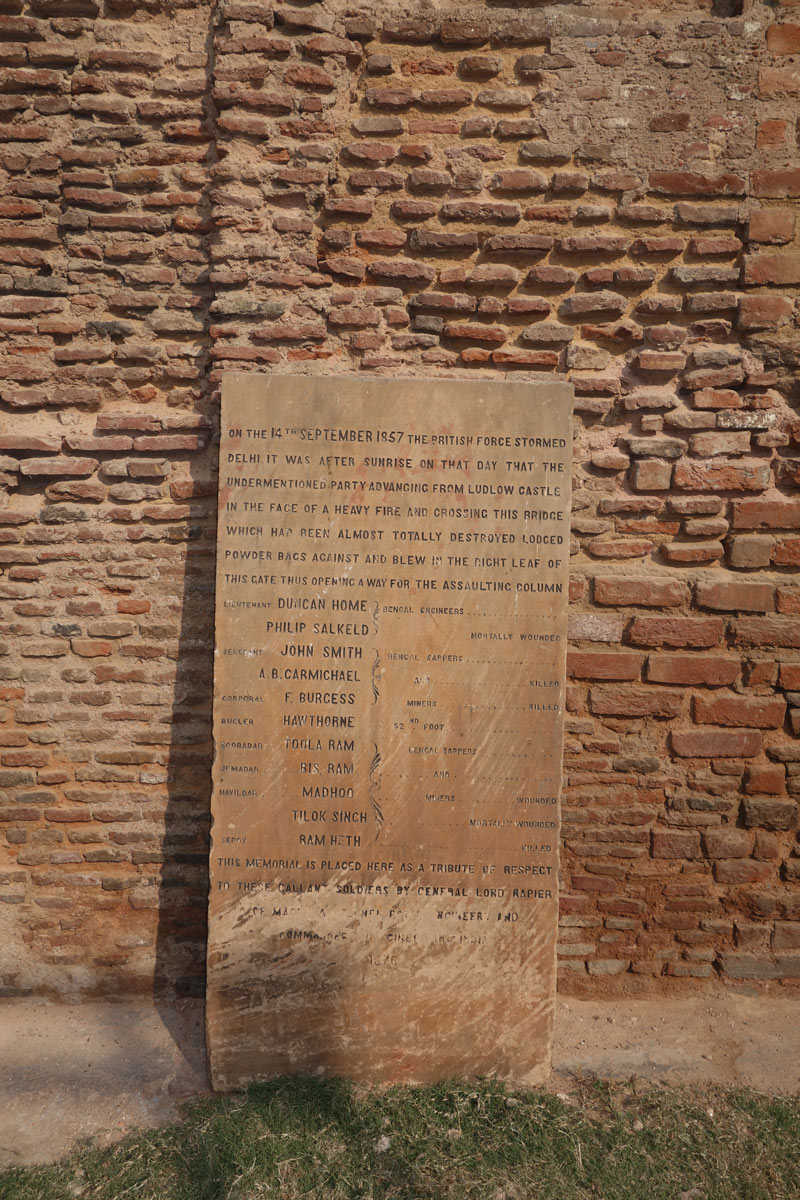

A poignant plaque with a moving message, listing the dead from 1857

A poignant plaque with a moving message, listing the dead from 1857