03 Apr Jaw-dropping Junagadh

Nature and history combine to make Junagadh a unique destination

The Junagadh hills rise dramatically from the flat Kathiawar landscape; that’s Mount Girnar with ancient Jain temples and Amba Mata on top

The Junagadh hills rise dramatically from the flat Kathiawar landscape; that’s Mount Girnar with ancient Jain temples and Amba Mata on topThe history of Junagadh is as old as the hills

Lets start at the very beginning…

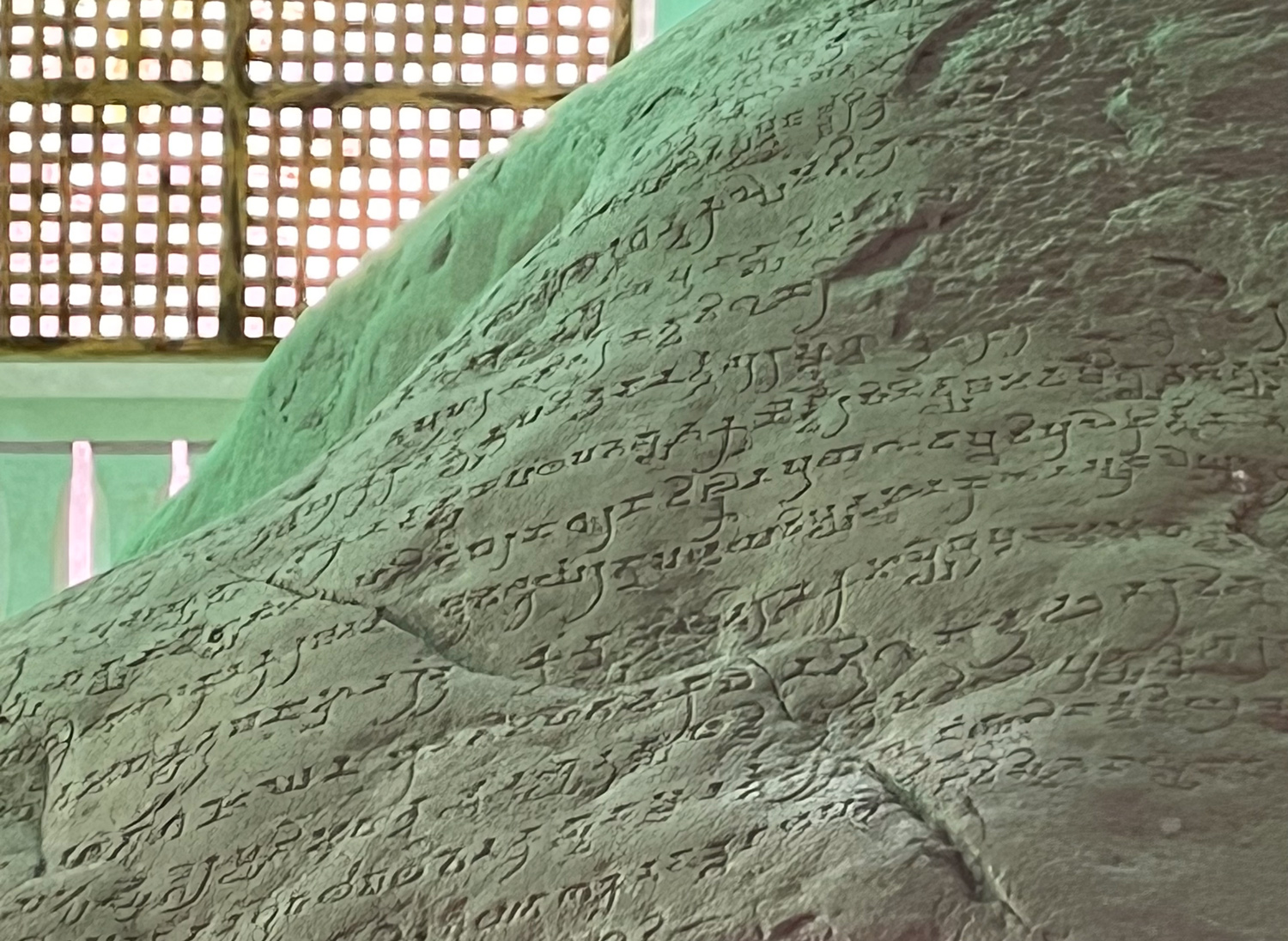

Emperor Ashoka’s rule over Saurashtra is attested to by his famous fourteen rock edicts, engraved on a granite boulder at the foot of Girnar hill.

Ashoka the Great (273-232BC) speaks to us with his engraved rock edicts

Ashoka the Great (273-232BC) speaks to us with his engraved rock edictsThe many treasures of Uparkot fort

It has a string of “must-sees” within its walls. First is the other-worldly Buddhist rock-cut caves that were carved during Emperor Ashoka’s period and may even pre-date the famous Ajanta and Ellora caves. These caves were carved from stone, going down 3 levels, and used as monks’ quarters eras ago.

The ancient Buddhist rock caves of Uparkot fort were cut from stone and used as monk’s quarters

The ancient Buddhist rock caves of Uparkot fort were cut from stone and used as monk’s quarters Rock-art from centuries ago; lions (top), apsaras (middle), elephants (bottom)

Rock-art from centuries ago; lions (top), apsaras (middle), elephants (bottom)The second step well, Navghan Kuvo, is older and deeper. What sets this vav apart is its ingenious system of managing the pigeon menace. The vav’s entry is pockmarked with little squares cut in the rock-wall, encouraging pigeons to rest here and not foray further into the deepness of the well. It seems to work, cleverly solving an annoyance as effectively today as it did centuries ago.

A solution to solve the pigeon menace is as relevant now as then

A solution to solve the pigeon menace is as relevant now as thenWhen Mehmud Begada conquered Uparkot to expand his Gujarat Sultanate, he converted a palace inside the fort in to a mosque, Jama Masjid. And beside the masjid is an interesting medieval canon, said to be built in Egypt, that was used in battle against the Portuguese in Diu in 1538. When the Portuguese won, the cannon was abandoned and later bought to Junagadh to be installed at the fort.

Mehmud Begada’s Jama Masjid within the fort was converted from a Rajput palace

Mehmud Begada’s Jama Masjid within the fort was converted from a Rajput palaceA heritage walk inside the old city

There are two types of structures to see; religious and palatial or administrative. Close to the fort is the city’s oldest Ram temple. I entered the temple complex, built in parts over different eras, to meet the well-spoken Rajnikant Agravat who explained the history of the temple to me. It was initially built in the mid 1600s by Govardhan sadhu who came here from Chittor in Rajasthan. At the time this was dense jungle. When the Babi nawabs started ruling from 1730, they became patrons of the temple and often visited themselves. Whenever threatened by invaders, the temple would be hidden and the nawabs erected a small sign so that devotees could find it. Rajnikant pointed out the sign to me; a round emblem mounted high on the wall, beside the road.

From here it’s a short walk to the Peerzada haveli. When the Babi nawabs established themselves in Junagadh they wanted a spiritual guide or advisor of distinction for their kingdom. They invited Pir Shamshuddin, a leader of the Syed community from the Kodinar dargah, near Somnath. He was given Peerzada house as a residence and his descendants still live here.

The Indiana Jones-like entrance to Peerzada haveli; magic and charisma

The Indiana Jones-like entrance to Peerzada haveli; magic and charismaThe entrance to the haveli has a distinct “Indiana Jones” feel to it; decrepit and run-down while also magical and charismatic. Across the road from the haveli are two small graveyards where the pirs are buried, including Pir Shamshuddin himself. Some of these little tombs are noticeable for their Junagadh dome, an architecture style that is distinct to this city – a bit like a squashed sphere which is set on a narrow drum and topped by a crown, with decorations and fluting running down it.

The Junagadh dome is unique to city; sits on top of a tomb for the pirs

The Junagadh dome is unique to city; sits on top of a tomb for the pirsThe Rang Mahal was the residence of the Junagadh nawabs. When the last of the Babi nawabs, Mahabat Khan III, left India for Pakistan in 1947 this building was taken over by the government. Sadly, it is today a skeleton of its former self.

The Rang Mahal was the nawabs residence ; its brilliant stucco-designs still sharp and arresting

The Rang Mahal was the nawabs residence ; its brilliant stucco-designs still sharp and arrestingSaving the best for last

The fantastical Bahauddin Maqbara is designed to astonish

The fantastical Bahauddin Maqbara is designed to astonish The Mahabat Khan Maqbara is next door to his vazir and friend Bahauddin

The Mahabat Khan Maqbara is next door to his vazir and friend Bahauddin Nawab Mahabat Khan II rests with his family members

Nawab Mahabat Khan II rests with his family membersHow to Get There :

- The closest airport to Junagadh is Rajkot (a 2 hour drive away on NH27)

- At Junagadh, I stayed at Hotel Bellevue Sarovar Portico, Station Road. It’s modern, clean and comfortable.

- You can cover most of the Junagadh attractions within a (long) day

- Within driving distance from Junagadh are several places of interest : the Gir forest, Somnath, Porbandar.