27 Apr India’s first Surveyor General’s legacy lives on in Bangalore

Born in a remote corner of Scotland, buried in Kolkata…the life and times of the remarkable Colin Mackenzie

In faraway Lews Castle museum in Stornoway in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides – 1,100 kilometers from London, to give one a measure of the region’s remoteness – an exhibition was underway on one of the town’s most famous sons, Colin Mackenzie. Consisting of materials on loan from various places, including the British Library in London, such an exhibition would be of little or no significance half-way across the world. Except that it is important, for India, in general; and for Bangalore and Nandi Hills, in particular.

Mackenzie’s watercolor of Nandidurg in 1791; a key site in the battle against Tipu Sultan

[Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colin_Mackenzie#/media/File:Nandidrug1791_Mackenzie.jpg.

The original is in the British Library Collection, London.]

Mackenzie’s watercolor of Nandidurg in 1791; a key site in the battle against Tipu Sultan

[Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colin_Mackenzie#/media/File:Nandidrug1791_Mackenzie.jpg.

The original is in the British Library Collection, London.]

In October 1791, Colin Mackenzie – who was then an officer serving in the East India Company – was present at the “Battle of Nundydroog” where he sketched this famous watercolor “View of Nundidroog with the Batteries firing on the Place during the Siege of 1791”.

It is an eerily accurate painting, almost photograph-like. Mackenzie has painted the puffs of white smoke towards the right of the canvas, from the mortars firing on to the summit’s double row of ramparts and ridges. One can also just about discern Tipu’s masjid in the foothills, which still stands today as a forlorn memory in Sultanpet village. And if you look more carefully, one can even plot, as a thin white line in the foreground left-of-center, the steps snaking up from Sultanpet to the top of the hill (‘Tipu’s Steps’) right up to the large round bastion at the summit.

Who was this man who drew up these nuances, with such an extraordinary effort and eye for detail?

Colin Mackenzie was India’s superstar Surveyor-General

Colin Mackenzie was born in 1753 to the Postmaster of Stornoway in the tiny Isle of Lewis in the Hebrides, a Scottish outpost with a population of a few thousand hardy islanders. He had secured a commission in the East India Company’s Madras Army, and arrived in Madras in 1783 aged about thirty. Once he set foot in India, he was never to see his homeland again.

Mackenzie was a keen mathematician, and eager to further “…his Oriental researches in India…(of) the knowledge which the Hindoos possessed of mathematics, and of the nature and use of logarithms” (Blake, p. 130). He was appointed to the Madras Army engineers and saw his first military engagement at the Third Anglo-Mysore War against Tipu Sultan from 1790-92. The leader of the British troops at the time, Governor-General Lord Cornwallis, noticed Mackenzie’s talents and proposed his appointment as a surveyor. Mackenzie never looked back, and his road to becoming the first Surveyor General of India (in April 1815) had begun.

Mackenzie was present at the iconic Battle of Seringapatam in 1799, when Tipu Sultan was finally defeated by the British and killed in battle. Over the next 10 years he led the Mysore Survey, mapping not only the geography but also the history and customs of the area, along with a team of trusted locals who formed his core group. His work led to the first detailed maps of the Mysore territory and it is said that Mackenzie’s intimate knowledge of South India was a key factor in the British military successes that followed.

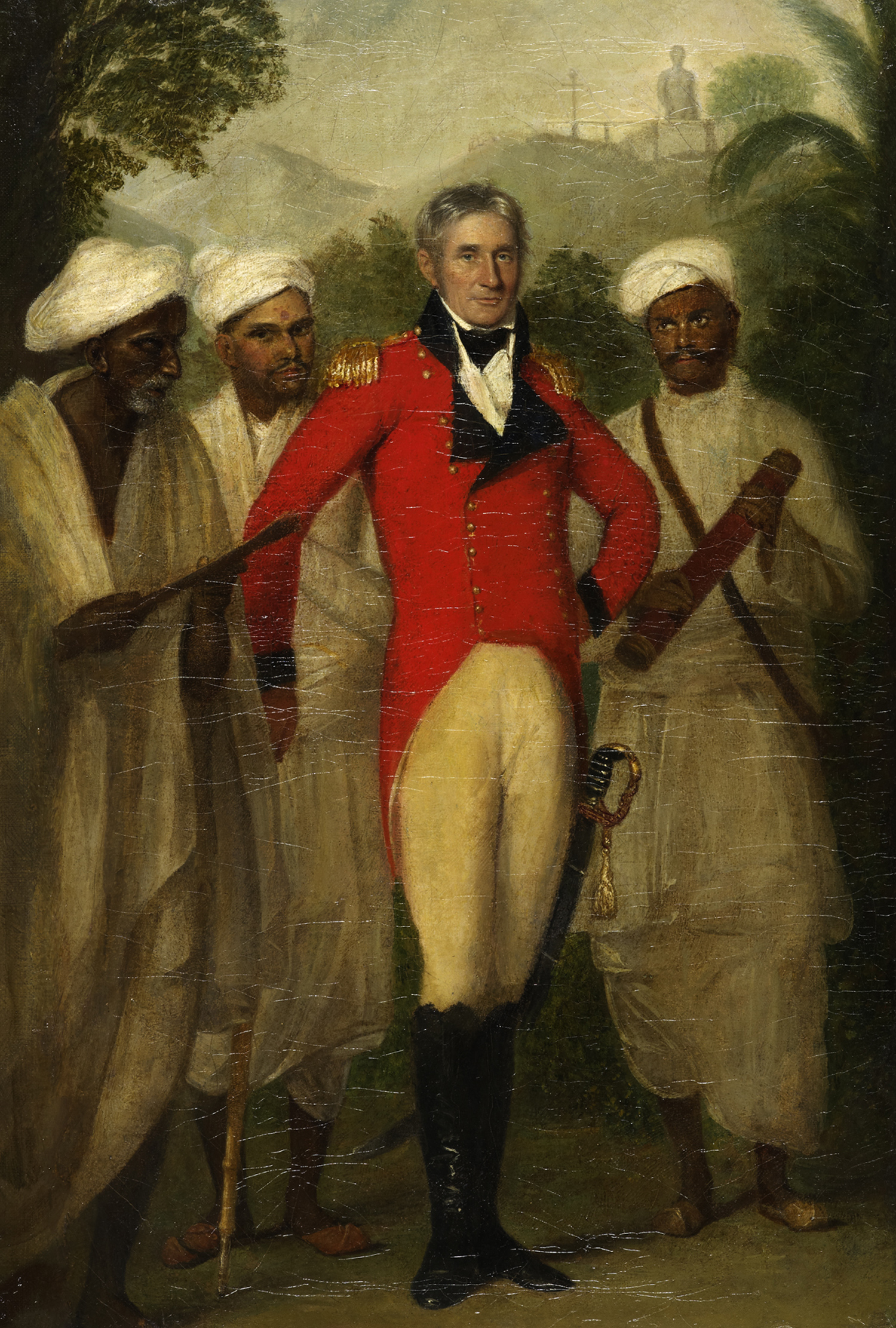

Mackenzie and his Indian staff

For all his efforts, Mackenzie relied heavily on his Indian staff with whom he had developed a close-knit, friendly team.

An 1816 portrait of Colin Mackenzie in his red East India Company uniform, flanked by his trusted Indian workers Dhurmia (extreme left), Venkata Lechmiah and his peon Kistanji holding a telescope. The Gomateshwara statue of Karkala is in the background.

[Source: http://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2017/09/spies-or-pandits-colin-mackenzies-indian-assistants-1788-to-1821.html.]

An 1816 portrait of Colin Mackenzie in his red East India Company uniform, flanked by his trusted Indian workers Dhurmia (extreme left), Venkata Lechmiah and his peon Kistanji holding a telescope. The Gomateshwara statue of Karkala is in the background.

[Source: http://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2017/09/spies-or-pandits-colin-mackenzies-indian-assistants-1788-to-1821.html.]

A key team member was Dhurmia, a Jain pandit who helped Mackenzie study the old Kannada language inscriptions and provided him insights into the Jain history of the region. And perhaps the most important was Venkata Lechmiah, a young Telegu Brahmin who’s elder brother Venkata Boria was earlier Mackenzie’s interpreter. When Boria died, the younger brother joined his team and became Mackenzie’s trusted go-to man with the “happy genius” of gathering information across all castes and expertly managing the rest of the team. So close was Mackenzie to his friend and colleague that when he died he left Lechmiah a portion of his estate in his will.

In 1815, Mackenzie was appointed the first Surveyor General of India and was transferred to Kolkata, with his headquarters in Fort William. Unfortunately, he was dogged by ill-health in his later years and died on May 8th 1821 at age of 68, after having spent a continuous period of 38 years in the harsh tropical climes of India, including a few years in Java in Indonesia. He is buried in Kolkata’s South Park Street cemetery, along with other notable British-India luminaries like Sir William Jones (founder of the Asiatic Society), Major-General Charles “Hindoo” Stuart, and Walter Dickens, the son of famed novelist Charles Dickens.

On his death, Mackenzie’s widow Petronella sold his extensive collection to the Bengal Government for a lac of rupees, considered then a “reasonable reimbursement”. The vast collection included “…1,568 literary manuscripts; 2,070 ‘local tracts’; 8,076 inscriptions; 2,159 translations; 69 plans; 2,630 drawings; 6,218 coins and 146 images and other antiquities”. Much of this treasure has been lost forever. But in a small castle museum in Stornoway, on the very edge of Scotland, they are still periodically showcased as bits of the fantastic collection of an Indophile with a difference from two centuries ago. Could we not ourselves be as protective of our land and its treasures?

Sources:

- “Illustrating India: The Early Colonial Investigations of Colin Mackenzie” (OUP India, 2010); by Jennifer Howes

- “Colin Mackenzie: Collector Extraordinary” (The British Library Journal, 1991); by David Blake

- long-form blog post by Sandeep Balakrishna drawing from both these and several other sources (including that edited in 2011 by Madras University’s Prof T V Mahalingam on Mackenzie’s manuscripts).

This article is by Siddharth Raja. A lawyer by profession and a heritage enthusiast by conviction, Siddharth lives in Nandi Hills, Bangalore and runs with his wife, Priya, a historical walking tour company ‘Nandi Valley Walks’ (www.facebook.com/nandivalleywalks).