17 Nov Finding Sir Thomas Roe

Emperor Jahangir’s drinking buddy is buried in a quiet London suburb

The sun dappled St Mary’s Church in Woodford; the final resting place for Sir Thomas Roe

The sun dappled St Mary’s Church in Woodford; the final resting place for Sir Thomas Roe  The graveyard at St Mary’s Church ; somewhere in here lies Sir Thomas Roe...

The graveyard at St Mary’s Church ; somewhere in here lies Sir Thomas Roe... The ancient door of St Mary’s Church; which Roe would have climbed to enter

The ancient door of St Mary’s Church; which Roe would have climbed to enterRoe first landed at Surat on 18th September, 1615 after an eight month sea voyage. He decided not to go ashore at once, mindful that his landing should be an occasion of dignity and splendor, setting the tone for his efforts in India. Disappointingly for him, Roe immediately got embroiled with the local Governor in an endless list of provocations and petty protocol ; on whether his goods would be custom searched, on whether the Governor would first call on the Ambassador or the reverse, on whether some of the gifts he had bought from England would be confiscated or not. To add to Roe’s annoyance, he also faced resistance from his own English trading factors, who sullenly refused his claim as the chief Company official in India. Roe spent an unhappy five weeks in Surat, and must have been glad to see the back of the city, leaving on the next leg of his journey to Burhanpur to meet with Jahangir’s second son Prince Parvez.

Burhanpur is on the northern bank of the river Tapti. It may today be a place of lesser importance, but at the time of Roe’s visit it was the seat of the Mughal administration for the Deccan and a headquarters for the army. The Lal Qila, or Red Fort, which was probably the scene of Roe’s presentation to Prince Parvez, is still in existence though much dilapidated. At Burhanpur, Roe had his first meeting with Mughal royalty, which he describes in detail. He was met by the Kotwal (police official) a mile short of the city, and taken to a caravan-serai (a lodging house for travellers) where he stayed a few days. On November 18th he was taken to meet the Prince…

“I went to his palace, taking with me such a present I thought might be grateful to him. I was received at the gate of the outward court, in which were a hundred gentleman on horseback, armed, and making a lane, through which I was to pass. The Prince himself sat mounted up in a round gallery, in the inner court, with a royal canopy erected over him, and rich carpets spread before him. As I drew near him, an officer came and told me, I must pull off my hat, and touch the ground with my bare head. But that sort of ceremony, though it might become his own couriers well enough, yet I upon the privilege of my character made bold to refuse it. Coming within the rails, to the steps of his throne, i did him that reverence that I judged agreeable; in return to which he bowed his body….all the Grandees stood on both sides of him, in the most humble posture imaginable, with their hands folded before them, as if they had been tied….as a more than ordinary favour, I was permitted to ease myself, by leaning upon one of the pillars that supported his canopy. Upon the whole, I must say, the Prince carried it to me in a manner sufficiently courteous and obliging”.

After Burhanpur, Thomas Roe reached Ajmer and first met Jahangir in January 1616. He spent two years at Jahangir’s court, between Ajmer and Mandu, passionately pushing his case for concessions to English trade. If Roe’s accounts are to be believed, the Emperor himself was well disposed, enjoying his company as a drinking companion and curious about the arts and culture of Roe’s England. However, Roe could not get over a chilly relationship with the rest of the powerful coterie in Jahangir’s court ; his influential wife Nur Jahan, his favorite son Prince Khurram (later Shah Jahan, of Taj Mahal fame), and Nur Jahan’s powerful brother Asaf Khan, “whose good will it was not so easy to secure”.

Together, they were inherently distrustful of English influence, for there were personal considerations involved. The Empress had her own commercial interests, extensively investing in trading expeditions and reaping handsome profits. This was threatened by the European powers, whose purpose it was to lure the trade of India in to their own ships. So, despite his efforts that spanned a number of years, Roe could only manage partial concessions for English trade. By February 1619, having more or less reached a dead-end, Roe terminated his appointment as Ambassador and set sail back to London.

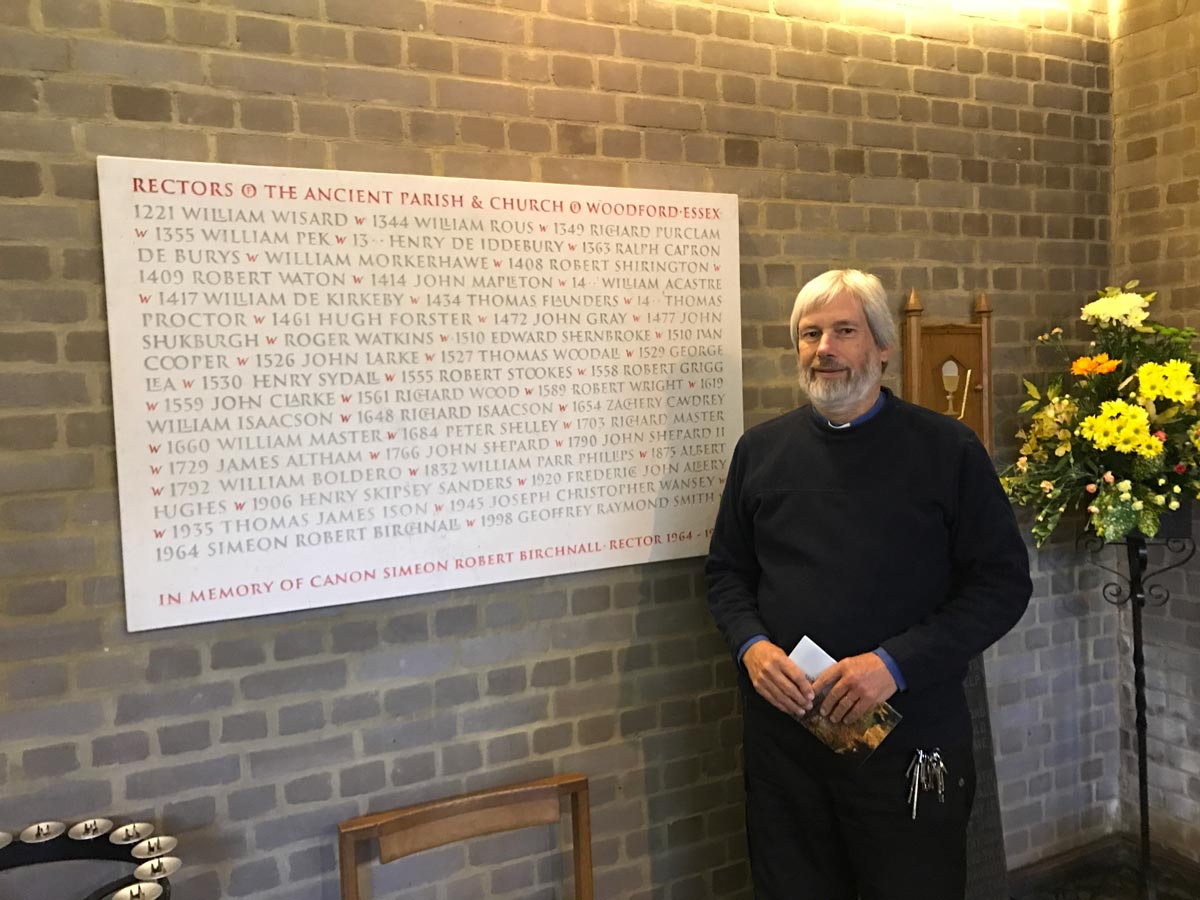

The kindly Reverend Canon Ian Tarrant, in front of his predecessors

The kindly Reverend Canon Ian Tarrant, in front of his predecessors** “Itinerant ambassador. The life of Sir Thomas Roe”. By Michael John Brown. Published by The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1970. Page 32

A day in the life of Jahangir

The captivating beauty of Lady Eleanor

* Page 254-256, “The Embassy of Thomas Roe to India 1615-1619”. Edited by William Foster, London. Printed by the Hakluyt Society.

An Ambassador’s wages

A King’s Flowery Speech

How to get here:

Information:

- Closest Tube : South Woodford (Central Line)

- Open from 8am to 6.30pm.

- Toilet facilities

- Wheelchair access

- Parking available on the road

Sources:

- “The Embassy of Thomas Roe to India 1615-1619”. Edited by William Foster, London. Printed by the Hakluyt Society

- “An account of Sir Thomas Roe’s embassy to the court of the Great Mogul”. Collected by John Harris. Published 1705.

- “Itinerant ambassador. The life of Sir Thomas Roe”. By Michael John Brown. Published by The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1970

- “Sir Thomas Roe and the Mughal Empire”. By Colin Paul Mitchell. Published by Area Study Centre for Europe, University of Karachi, 2000

- St Mary’s Church, Woodford, Essex : Archive Book