14 Oct Agra beyond the Taj : The Tomb of Itmad ud Daulah

There is a Jewel Box to discover in Agra. And it’s not the Taj

The tomb of Itmad ud Daula sits, delicate as a jewel box, on the banks of the Yamuna River at Agra.

It was built by Nur Jahan in memory of her parents, who died within a few months of each other at Agra in 1622. Nur Jahan’s father, Mirza Ghiyas Beg, also the grandfather of Mumtaz Mahal (of Taj Mahal fame), was the vazir of Emperor Jehangir.

When Nur Jahan built this, she was the richest woman in the world. And this is her finest creation.

It is the first Mughal tomb to be built of white marble (being Nur Jahan’s favorite color), instead of the red sandstone preferred earlier, and is the inspiration for the Taj Mahal which followed some decades later.

The jewel-box like tomb of Itmad ud Daulah: “the Mughals began like titans and finished like jewelers”

The jewel-box like tomb of Itmad ud Daulah: “the Mughals began like titans and finished like jewelers”

Who was Itmad ud Daulah?

Mirza Ghayas Beg (he later given the title Itmad ud Daulah) and Asmat Begum, both of whom are buried in this mausoleum, were from Persia. They were the parents of Nur Jahan.

Ghayas Beg (1544-1622) was born in Tehran to a dignified family of nobles, who had unfortunately fallen on hard times. As a young man, Ghayas decided that his future lay best outside of Persia, and so, leaving behind his ancestral land, he joined a caravan that was making a journey to India – together with his young family and a pregnant wife.

On the way, near Kandahar, Nur Jahan was born. Her parents named her Mehr-un-Nisa (the moon of womanhood). There is an often-told legend about how, a few days after her birth, a giant cobra coiled itself around the infant Mehr protecting her from danger. Though there is no historical evidence, it’s a story that has embellished itself in folklore.

In 1579 Ghayas arrived in Agra. Luckily for him, the man who led their caravan, Malik Masud, was an influential trader who knew Emperor Akbar and counted his powerful ministers and royal ladies of the zenana as clients. There are stories of Masud selling Persian carpets to Raja Man Singh for 2 lacs, and shawls and chandeliers to the first lady, Harka Bai, and others at the zenana*.

So Ghayas Beg was granted an audience with Akbar, who liked his refined manners and offered him a job in his administration. There was no looking back. In a few years, Ghayas was appointed the diwan (treasurer) of Kabul, and when Jehangir followed Akbar as emperor, his stars shone even brighter; he became the wazir ((prime minister), was given the title Itmad ud Daulah (Pillar of the State) and his daughter Mehr-un-Nisa married Jehangir (her second marriage) to become the Empress of India.

The rise and rise of Mehr-un-Nisa…

Mehr-un-Nisa, by now perfectly educated in Persian arts and letters, was married at the age of seventeen to an Afghan noble Ali Quli – the match organized by emperor Akbar himself.

Ali Quli, who was given the name Sher Afghan for his bravery in killing tigers, was posted in Burdwan in Bengal as a jagirdar, where he lived with his young wife. The couple were blessed with a daughter, Ladli Begum. Sometime in 1605, after eleven years of marriage, Sher Afghan was killed in a sword fight (he is buried in Burdwan at the mazhar of Pir Bahram Sakka) and Mehr, at the young age of thirty, was widowed. She returned to the Mughal court, where by now Jehangir was emperor, and her father and brother held senior positions.

For several years Mehr lived a quiet life in Agra, till in 1611 a besotted Jehangir saw her and proposed marriage. It was the union of two mature individuals; Jehangir was forty-two and Mehr was thirty-four. The much-married Jehangir had many previous wives, but Mehr was to be his last. She was given the title Nur Jahan.

Mehr becomes Nur Jahan, Empress of India

Jehangir’s relationship with Nur Jahan massively shaped his reign. Seeing her talent and charisma, he was happy to let her lead, with Nur Jahan “…issuing royal firmans, having gold coins struck in her name, engaging in trade…(building) a series of magnificent buildings through the breadth of the empire…”**

For fifteen years, Nur Jahan – politically astute, sophisticated, assertive – was the de facto ruler of Hindustan. She excelled in international trade, creating such wealth as to become the richest woman in the world (which is not surprising, given that the Mughals had made India the world’s biggest economy), and she deployed these riches for sponsoring buildings and cultural events on a scale not seen before. When Itmad-ud-Daulah died in 1622, Jehangir awarded his entire estate to Nur Jahan making her even more fabulously wealthy.

But all this power also attracted enemies. As Jehangir became increasingly ill, and different factions swirled around the ailing emperor staking a claim to the Mughal throne, Nur Jahan lost out. And in 1627, when Jehangir died and Shah Jahan became the emperor, she retired with her daughter Ladli Begum to Lahore to live out her remaining years. Though provided a generous allowance of two lacs a year, Nur Jahan requested that “on her grave be placed neither a candle nor a flower”*; she wished to be laid to rest, like she was born, unfussed and quiet. She died in 1645 and is buried in Lahore.

But before she leaves, Nur Jahan built the most beautiful mausoleum for her father, the tomb of Itmad-ud-Daulah at Agra. It is an exquisite jewel-like building that is one of a kind.

Nur’s masterpiece: “the Mughals began like titans and finished like jewelers”

The moment I stepped through the ornamental gateway of Itmad ud Daulah’s tomb complex, my camera was on overdrive.

It’s difficult to explain how jaw-droppingly beautiful the first look of this building is. Set in the center of a Charbagh style garden, the tomb is pure white, elegant, jewel-box like, built in perfect symmetry and graceful proportion. Despite its size, the building looked as delicate as an egg-shell.

The garden tomb of Itmad ud Daulah; despite its massive proportions, looks as delicate as an egg shell

The garden tomb of Itmad ud Daulah; despite its massive proportions, looks as delicate as an egg shellThe best way to explore the complex, and to understand its context, is by walking around the building and towards the back, beside the flowing Yamuna river. This was the original riverside entrance, accessed in Mughal times by visitors rowing across the river from the main town on the other bank.

Agra was a riverside city, built on two sides of the Yamuna river. On the western bank was the main town, including the massive Agra fort and later the Taj Mahal. On the eastern bank were a series of gardens, with one of these being the tomb of Itmad ud Daulah.

Visitors would alight at a double-storeyed pleasure pavilion, which served as the main entry gate and overlooked the river. There are plenty of interesting features on its façade; the famous chini khana design – that embellish the walls of so many Mughal monuments – small niches carved in the walls and used for displaying decorative objects, often Chinese porcelain (hence the name). Frescoes of floral patterns on the walls and ceiling, along with the surprising use of the wine-vase and dish-and-cup designs.

The riverside entry gate, overlooking the Yamuna River, built as a pleasure pavilion- notice the wine-vase designs on the top corners

The riverside entry gate, overlooking the Yamuna River, built as a pleasure pavilion- notice the wine-vase designs on the top corners Through this pavilion we enter the Charbagh style garden, divided in to four equal quarters with shallow water channels and paved pathways. During the Mughal era, this garden would have been a lush and perfumed space with flowing water, the fragrance and shade conveying a sense of eternal life. The British preferred flat lawns instead, which is largely how it stands now.

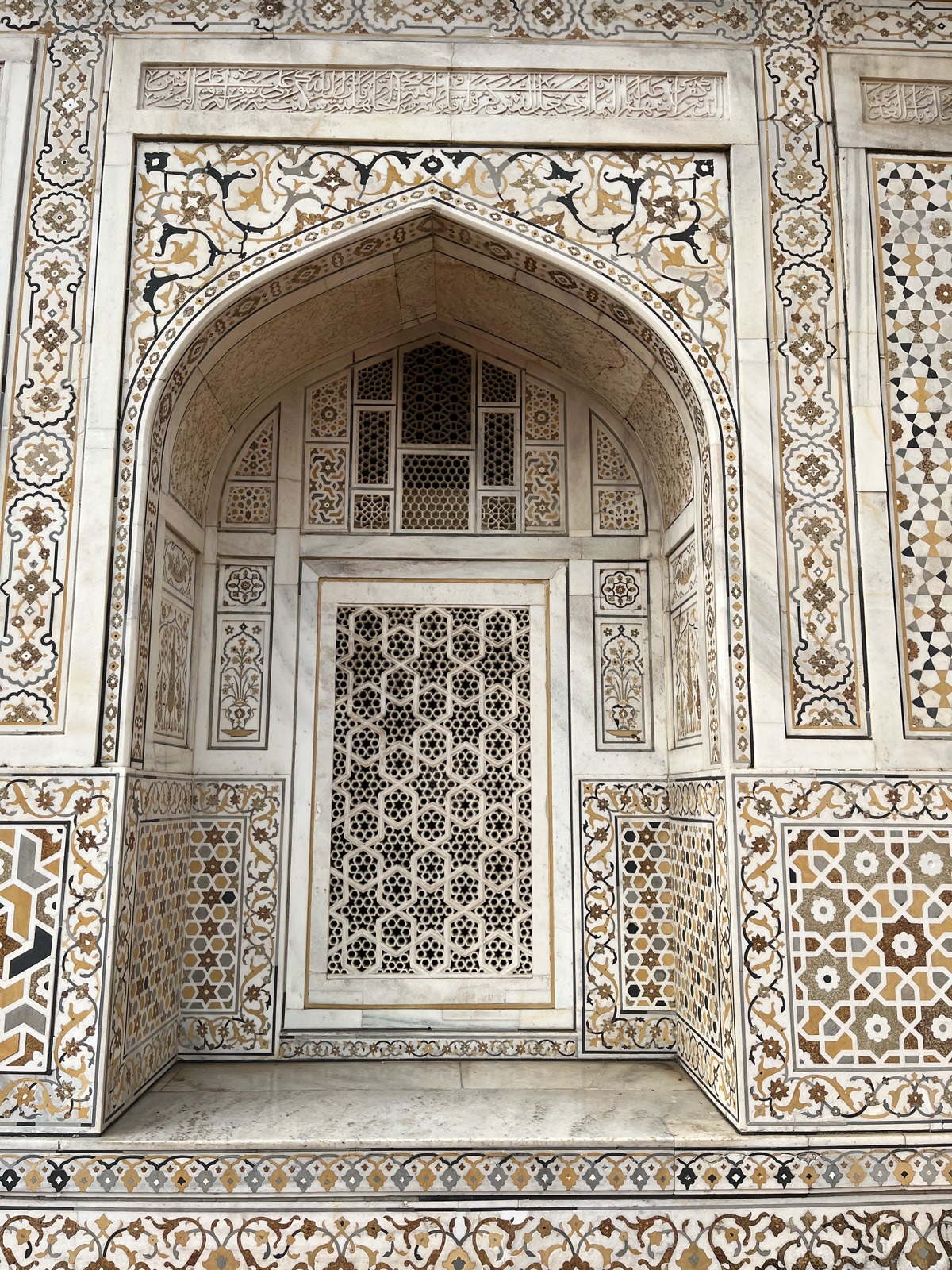

The tomb is at the centre of the garden, its ornamentation breath-taking. Every inch is covered in fine stone-inlay Pietra dura work, also called prachin kaari. The inlay work is in jasper, lapus lazuli, onyx, topaz. There are Persian-inspired wine vessels, fruits trays with grapes and pomegranates, water ewers, cypress trees, honeysuckle, lotus. Even the floors have stone inlay work in striking geometric patterns. Light and air is filtered in through exquisitely carved jaali panels, like “embroidery work done in ivory”.

Pietra dura stone inlay, jaalis, geometric patterns, floral pattens…

Pietra dura stone inlay, jaalis, geometric patterns, floral pattens… Cypress, honeysuckle, a paradise garden

Cypress, honeysuckle, a paradise garden Persian inspired wine vessels, fruit trays, water ewers

Persian inspired wine vessels, fruit trays, water ewers Inside the building are rooms and interconnected doorways with the graves of family members, Quranic verses engraved on them. As per custom, the male graves have a raised kalamdaan (pen box) symbol on top, while the female graves have a flat takhti (slate) design.

In the center are the caramel-colored graves of Mirza Ghiyas and Asmat Begum, resting in quiet elegance.

In the central chamber, graves of Nur Jahan’s parents Mirza Ghayas Beg and Asmat Begum

In the central chamber, graves of Nur Jahan’s parents Mirza Ghayas Beg and Asmat Begum Resting eternally in quiet elegance

Resting eternally in quiet eleganceIt is no wonder that Itmad ud Daulah’s tomb is described as a jewel box, and considered Nur Jahan’s most beautiful creation. The ASI plaque at the entrance to the monument describes it as one of the most “gorgeously ornamented Mughal buildings…testifying that the Mughals began like titans and finished like jewellers”. They have got it right.

The ability to conceive of this beauty, and then execute it to such perfection and attention to detail, in a setting as grand as the banks of the Yamuna, makes it a must-see, and one of the finest examples of Indian architecture.

* “Jehangir”. By Muni Lal, pg 125, 129, Preface

** “Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens & Begums of the Mughal Empire”. By Ira Mukhoty.

How to get here:

While driving from Delhi to Agra, exit off the Agra Expressway and on to National Highway 21 (also called Hathras Road)

Drive past the Ram Bagh Chauraha

Follow the signs for Itmad ud Daulah’s Tomb

Information:

- Parking is available on the main road

- A parking ticket costs Rs 50/-, and an entry ticket Rs 30/-

Sources:

- “Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens & Begums of the Mughal Empire”. By Ira Mukhoty. Published by Aleph Book Company.

- “Agra: The Architectural Heritage”. By Lucy Peck. Published by Roli Books, 2008

- “Jehangir”. By Muni Lal. Published by Vikas Publishing House

- “The Travelers Guide to Agra”. By Satya Chandra Mukerji. Published by Sen & co, 1892